Hip priest

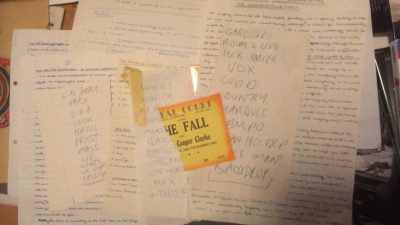

‘The Fall make you think. The consistent unconformity of their barrage of controlled anarchy coupled with Mark Smith’s words, attitudes and expressions make the perfect recipe for a deep-rooted paranoia and feelings of inadequacy, which is how music, any music, should be. The Fall’s music disturbs me, it’s not easy and it nags uncomfortably with a harsh insistence that no other band I know can do, which is why I love their music so much’. Those recently rediscovered words were written in scrawly schoolboy hand-writing sometime during the early hours of Wednesday November 4th 1981. This was shortly after I arrived home from seeing The Fall play at The Warehouse, a black-painted club in Liverpool since destroyed by fire. It was my third time of seeing The Fall over the previous eighteen months. I’d recently got into the habit of sloping home and penning screeds of earnest reviews of them, with neither hope or clue of how they might be published. Despite the misuse of the word ‘unconformity’, which I’ve just found out is something to do with rock masses and erosion, and a masochistic adolescent hunger to have my senses shaken up, I reckon what the seventeen-year-old me wrote pretty much spot on.

I was fifteen the first time I saw The Fall. I saw them play umpteen times in the thirty-seven years that followed. trudging with blind faith between concert hall and sweaty club as their fortunes ebbed and flowed. Often they were brilliant. Sometimes they were a mess. But even if and sometimes because Mark E Smith, the group’s sole constant, wilfully sabotaged the night, they were never dull.

It was a suitably stormy Wednesday night when the news broke of the death of Smith, who drove his group with the obsessive intensity of a tyrannical actor-manager, a despotic general or a nineteenth-century factory owner.He looked like a snot-nosed and scrawny dole-queue version of Billy Casper from Kes after he’d learnt to read and stand up for himself. The young Mark E Smith might well have been the model too for Johnny, the chippy, self-destructive and disaffected smart-arse played by David Thewlis in Mike Leigh’s Naked. As he aged, Smith appeared to have morphed into a Frankenstein’s monster combining Gene Vincent, Antonin Artaud and Kurt Schwitters, taking Dadaist stand-up to the masses.

Smith’s passing was one of those where-were-you moments. It was the same when Prince died. Bowie and Leonard Cohen too. Except this was Mark E Smith. That wasn’t a club he’d want any part of. Not out of humility, you understand. He’d have likely thought such crocodile tears for fallen idols was ridiculous beyond belief. He might have been right.

At the risk of invoking Smith’s beyond-the-grave wrath, I was sitting in the upstairs foyer of the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh checking my phone just as the news broke on social media. I was waiting for the doors to open for a live music night called Amuse Bouche happening in the bar downstairs. Amuse Bouche is a new regular world music night, which that night featured a Syrian duo playing a short set, as well as a trio called Fareeble, who played East European Jewish Klezmer.

Playing double bass in Fareeble was Emma Smith, who also organised the night. Emma plays in loads of bands, and also runs another night called Bitches Brew, which features performances solely by women musicians. Emma used to play bass with Gorillaz, the virtual band made flesh by Damon Albarn and cartoonist Jamie Hewlett. I found out much later that she played with them at a Gorillaz show I was at, a trailer for the first Manchester International Festival in 2007. Gorillaz played their second album, Demon Days, in full. Most tracks on the album featured a guest vocalist of some repute, including the likes of Shaun Ryder and Ike Turner. Not everyone made it, but anyone who can get Shaun Ryder in the same place on time every night for five nights deserves a medal.

Gorillaz did something similar on their third album, Plastic Beach. Mark E Smith was one of the guests on the record, providing lead vocals on a song called Glitter Freeze, which he performed live with Gorillaz at Glastonbury and elsewhere. When I start telling Emma about Smith’s passing, I only remember all this mid-way through the telling.

“I won’t expect you to play a cover,” I say to Emma just before she goes onstage with Fareeble.

“It’s alright,” she says back. “I’ll just swear.”

A couple of days later after I’ve been watching YouTube footage of Gorillaz and Smith at Glastonbury, I message Emma to confirm that was her playing double bass. When she gets back, not only does she say it was, but she tells me the sort of MES story that has become legend. It’s about how, when Gorillaz played Dublin, Smith got in trouble for smoking on the bus outside the band’s hotel. He’d apparently tried to hide his fag under the table, but held it directly under the cup hole, so the smoke rose up straight through it. Like a naughty schoolboy in denial, Smith affected not to know how the driver knew it was him.

This is classic Mark E, rebellious, hapless and unrepentant in the same breath. It’s one of a million one-liners that will eventually be knitted together into a monster narrative collage that probably won’t sum up his crazed genius.

It was the same when The Fall played at the inaugural Manchester International Festival itself. They were head-lining an old dance-hall and Manchester institution called The Ritz, immortalised in John Cooper-Clarke’s poem, Salome Maloney. The gig had been programmed in part to coincide with the launch of Perverted by Language, a collection of short stories named after The Fall’s 1983 album, their sixth. In the book, various authors took a Fall song title as inspiration for whatever they wrote.

Before the gig, Alan Wise, who managed The Fall at various points over the years came out in front of a packed audience. Like the Ritz, Wise was a Manchester institution. Having also managed ex Velvet Underground chanteuse Nico during her brief stay in the city in the 1980s as well as Cooper-Clarke, also on the Ritz bill, one suspected Wise possessed the patience of a saint.

Wise sported an Our Man in Havana hat and the perennially amused, terminally cocky air of someone following orders. In getting to be the messenger you couldn’t shoot, he resembled a wrestling manager as much as a post-punk masochist Mr Fixer. Wise informed the packed throng of devoted Fall-watchers that Mark E Smith had advised him to say that he totally disowned the book they were there to help launch, and that they probably shouldn’t buy a copy. For long-term Fall fan and contributor to the book Stewart Lee, who read his work out alongside other contributors, Wise’s statement must have galled.

I was with a colleague and my then girlfriend, neither of whom knew anything about The Fall. I took a certain pride in acting as a guide to the group’s foibles. No, Mark E Smith isn’t just a drunk, I said, although – and I heard the smugness in my voice – that is a brand new band onstage. The high turnover of Fall members had become the stuff of legend, and the American group who’d made up Smith’s charges until recently had clearly moved on.

Back when I was fifteen, seeing The Fall for the first time, I doubt I would’ve been anywhere near as blasé. The gig was in an old cabaret club called Mr Pickwick’s, where, most nights, wanna-be Tony Christies strutted their stuff to a smart-but-casual crowd munching on chicken-in-a-basket. It was May 1980, a Wednesday night, and by rights I should’ve been at home revising for my exams before leaving school the next month to become an office monkey with British Rail, in what was then called a Youth Opportunities Programme.

I’d bought a ticket for £1.25 at Probe, Liverpool’s in-crowd hippy/punk record shop, and The Fall were head-lining a triple bill of what was supposed to be made up of The Passage and Crispy Ambulance. As it turned out, The Passage didn’t appear, and were replaced by Felt. A legend in his own right, Felt’s singer and driving force Lawrence told me years later in an interview that night was their first gig as a full band. He told me how he’s said something to Smith about how he was going to be famous, which apparently made MES laugh like a drain.

Despite the ticket saying the doors weren’t opening until 8pm, for some reason I went down at 6. I’d only been to a handful of gigs before, and while I was none the wiser, neither did I want to risk missing anything. Nor did I understand that night-clubs, even chicken-in-a-basket cabaret dives, were late-night emporiums of pleasure. It was quite a blowy May, and, standing in the ‘queue’ in the club car park for the next couple of hours, it got proper parky. In the end the doors didn’t open till after 9, which was probably about right.

Seeing Mark E Smith onstage for the first time was as thrilling as witnessing anyone in the flesh who you only know from pictures. The British music press, NME in particular, was in full throes of its post-punk golden era, and Smith was already giving assorted addresses to the nation in a series of increasingly expansive interviews.

I recognised most of the band from pictures on the back cover of The Fall’s second album, Dragnet, which already featured a completely different line-up from its predecessor, Live at the Witch Trials. Only the drummer was different here in a line-up I now know was made up of Marc Riley on guitar and keyboards, Craig Scanlon on guitar, Steve Hanley on bass and his kid brother Paul, who was about my age, the new drummer.

According to my teenage notes (no reviews yet), written on pages 3 and 4 of something I somewhat grandly called ‘Evenings of Musical Entertainment’, The Fall did nine songs, plus two encores, with two songs in the first encore and one in the second. I recognised Dice Man, Chock Stock and Flat of Angles from Dragnet, plus the singles, Rowche Rumble and Fiery Jack. I must’ve known New Puritan a bit as well from John Peel playing the version on the live album, Totale’s Turns. The record wasn’t long out, and New Puritan was more like a vitriolic state-of-the-nation address than a song. Maybe Peel had been playing How I Wrote ‘Elastic Man’ as well. I’ve got it written down, anyway, though it didn’t come out as a single yet for a couple of months yet.

Beyond my notes, what I remember vividly most of all is Smith himself. Barely looking anyone in the eye, he paced the small stage imperiously, sneering at both his band and the audience with contempt, somehow managing to turn his back on both. Where the few other bands I’d seen all struck some kind of pose to try and look cool, Smith’s scruffy anti-star stance made him look possessed, like some old-before-his-time cult leader wired on speed.

The group kicked into a hypnotic and potentially endless keyboard-led riff on a song I’d later know as New Face in Hell when it was broadcast as part of The Fall’s third Peel session in the autumn. Mid-way through its splenetic conspiracy theory narrative, Smith flicked a sly lizard glance at the band before pulling a kazoo from his pocket, blowing with a fury that matched his proclamations. At other points he would hold a Dictaphone up to the microphone, playing a recording of his own voice. At the end of one song, he gave Paul Hanley’s bass drum a swift kick to make him abruptly stop playing, as if his charges had gone over the time limit of what was allowed. It was a shocking moment.

This wasn’t what pop singers – even post-punk pop singers – were supposed to do. This was about power, control and manipulation of both audience and band. It was like being at some kind of cult-based rally, being harangued into submission by a precocious hellfire preacher who, with the aid of the musical earthquake he’d constructed behind him, was going to pulverise our sins away. It was as thrilling as the shows that followed, when The Fall – and Smith – seemed to grow in intensity as they built up to Grotesque, Slates and Hex Enduction Hour in a way captured best on the Live in London 1980 cassette released in 1982. By that time, time Smith had re-introduced The Fall’s original drummer Karl Burns back into the fold to play alongside Paul Hanley. This two-drummer line-up gave Smith’s increasingly opaque constructions even more dramatic power. Power. That word again.

There was always something deeply theatrical about Mark Edward Smith. That was the case from that first shocking kick of Paul Hanley’s bass drum, to much later, when this most self-destructive of band-leaders would mess up the sound-levels, turn the group’s amps down or off. Latterly, he’d lean on Poulou’s keyboards, making a tuneless din like some bratty toddler spoiling it for everyone else in the kindergarten music room. Even the way he was pushed onstage in a wheelchair at what turned out to be The Fall’s final gig in Glasgow last November made him look like a Shakespearian king reclaiming his throne.

That level of controlling the onstage action, with Smith effectively becoming a director, shoving the scenery around to keep everybody on their toes, reminded me of the sorts of things Polish theatre director Tadeusz Kantor did. Kantor was an avant-garde legend who also liked to create and then reassemble stage pictures while everyone was onstage. Kantor worked a lot with marionettes. I guess they’re less likely to answer back or punch you in the face than a frustrated drummer might. There’s something there too about Gustav Metzger’s notion of auto-destructive art, which inspired The Who’s Pete Townshend to smash up his guitars onstage. Jimi Hendrix might have picked up on it as well when he set fire to the American flag, redefining the electric guitar as he went.

The only time Smith’s onstage interventions didn’t work was when he played with Andi Toma and Jan St Werner, aka Dusseldorf-based electronic duo Mouse on Mars, as Von Sudenfed. How Smith got involved with them I’ve no idea, but they did one album together in 2004. When they played live in Edinburgh, Smith tried his usual messing about with the levels, twiddling various knobs when he thought Toma and St Werner weren’t looking. But of course they were, and you could see that, unlike Smith’s regular and more luddite band-mates, they were more amused than annoyed by his antics. These were techno boys, and could just absorb it all and turn it into a twisted electronic melody. Maybe that was Smith’s idea all along. Possibly in a sulk, he finished the set unseen from the stairwell anyway.

There’s some footage on YouTube of The Fall from 1995 rehearsing a cover of Electric Light Orchestra leader Jeff Lynne’s song, The Birthday, first done by Lynne’s trippy 1960s band, The Idle Race. The Fall’s then seven-strong line-up features an all-female front-line. This features returned guitarist and ex-wife of MES, Brix Smith, guitarist/keyboardist Julia Nagle and Smith’s then girlfriend Lucy Rimmer on lead vocals. While the politics of this are fascinating enough, the real eye-opener comes watching how Smith conducts himself. Gnomically pacing the room, fag in hand, he offers gentle instructions to the band, nudging them along, eking out nuances for the arrangements as he goes. Given the chaotic few years that would follow, with Nagle the only other person in the room besides Smith to survive in the band beyond 1997, it’s an oddly calm snap-shot of a group’s working process. It also reveals Smith operating here as a theatre director as much as musical arranger.

Given that he’d already written and directed his own play, Hey! Luciani!, at the Riverside in London a decade or so before, perhaps this should come as no surprise. Featuring a live score by the group, who also took speaking parts alongside choreographer Michael Clark and performance artist Leigh Bowery, Smith penned a free-form conspiracy-based drama around the mysterious death of Pope John Paul I. Most who saw it were baffled, but the title song made a great single.

Two years later, The Fall appeared at Edinburgh International Festival, playing the live soundtrack to Clark’s ballet, I Am Curious, Orange. Clark had previously danced to recordings of The Fall, recognising the band’s primal rhythmic pulse on early works such as New Puritans, which took its title from Smith’s song. I Am Curious, Orange was an ambitious and irreverent large-scale mash-up of bare bums, giant hamburgers, a football match and outlandish costumes that were works of art in themselves. Smith took one of the dancers, Ellen Van Schuylenburch, on tour, and it’s fair to assume he picked up a few things from Clark and co in terms of drama.

This grammar school drop-out’s auto-didactic tendencies had already seen him absorb a mix of existential gothic and speculative fiction which had seeped into his own work. Many of his lyrics – New Face in Hell, Spectre Vs Rector and Jawbone and the Air Rifle among them -were narrative-led play-lets peopled by Hogarthian grotesques reimagined in late twentieth century Salford. Sometimes Smith wrote in character, such as Roman Totale XVIII, ‘Honorary Member, Wakefield Young Drinkers Club’ as the sleeve of Totale’s Turns, named in his honour, would have it.

The album was recorded before an ‘80 per cent disco weekend dating audience,’ according to Totale’s sleeve-notes, in various northern English working men’s clubs. Here, a ‘turn’ is parlance for the acts that usually make up the cabaret in-between the bingo and the buffet. Later, the now deceased Totale provides the sleeve-notes – ‘Didactic discourse from the shell of R.Totale’ – for Grotesque (After the Gramme), as edited by ‘J.Totale, vicious son’ who Smith has narrate that album’s closing epic, The N.W.R.A.

Beyond dramas real and imagined, for me, those first Fall gigs, at Mr Pickwick’s, Gatsby’s and three at the Warehouse, opened up whole new worlds. On record, this moves from the Peel session version of New Face in Hell to Leave the Capital and Slates, Slags etc on Slates, to pretty much everything on Hex Enduction Hour. Much later, there’s the machine-age cover of Lost in Music to Theme from Sparta FC to Blindness and beyond. Each one is driven by the same sort of relentlessness that powered Mother Sky by Can or the Velvet Underground’s What Goes on in the version captured on Live 1969.

Then there are the slow-burning epics. Music Scene, A Figure Walks and Spectre Vs Rector. Hip Priest, later reinvented with glam racket bounce for I Am Curious, Orange as New Big Prinz. There is The N.W.R.A., And This Day and a million others that seemed to take Smith’s maxim in the lyrics of Dice Man to the limit:

‘They say music should be fun

Like reading a story of love

But I wanna read a horror story’

And there was the realisation that an album recorded in just one day in a cheap studio can be more astonishing than anything a bunch of muso bores take six months over.

There are raw manic pop thrills too, like hearing Just Step Sideways live for the first time, segued in by C’n’C and followed by a blistering Session Musician, with Smith just a couple of ear-piercing feet away. There were the shiny silver shirts at Barrowland, the way Smith nearly brought a lighting rig toppling down on Calton Hill, and how a few short years after being at the King’s Theatre in the Edinburgh International Festival, The Fall ended up playing the city’s tiny Cas Rock pub.

There were the nights when it was touch and go, when band and singer looked like they hated each other, when it might have exploded into a punch-up any second. There was the show at the Venue when another girlfriend uninitiated in the ways of The Fall, was so appalled by how unwell Smith looked that she left half-way through. More fool her. She missed Smith bring on Manchester soul singer Dougie James for a killer encore of New Big Prinz. There was the way Smith mischievously shoved a bouncer out the way on the Renfrew Ferry, and the way Smith and Elena shared a loving glance towards the end of a Queen’s Hall show as he leaned his elbow tunelessly across her keyboard. And how about that gig at Studio 24 that was over after 25 minutes, or the night at the Picture House when he went off and Elena said he had bad feet, just before some radge jumped onstage and did quite a passable impression of him. Or what about that other time, donkeys years before, when Gordon Legge read his hilarious story about a crazed job interview, Question Number Ten, at the Out of the Blue gallery when it was on Blackfriars Street, and the first line is ‘Name fifty singles by The Fall’.

There was that time in Reykjavik, when my friend Benni pointed out the wraith-like figure of Megas Jonsson, regarded as the father of Icelandic rock music, and name-checked years before in The Fall’s song, Iceland, which they recorded in a cave and which ended up on Hex Enduction Hour. Jonsson had been banned by the authorities, and had quit the music business to work on the docks. Smith became fascinated by someone he recognised as a kindred spirit, shook his hand at a gig there, and ended up going home with a bag-load of Jonsson’s records. Seeing a bunch of his CDs displayed in a stall in the Reykjavik market, I thought about doing likewise, but reconsidered after Benni played me some of his more recent stuff.

Last year, after a daft online conversation with stage designer Neil Warmington, I free-formed a three verse homage to Scottish contemporary theatre classic, The Steamie, in the style of Smith circa ’81-‘83. Fun as it was to do, it doesn’t even come close to Smith’s contrary, belligerent and wilfully oppositional spirit.

The Fall occupied a mysterious and unique place where the avant-garde and pop culture met, with Smith casting himself by turns as alchemist, sooth-sayer and provocateur. He was also a comic wind-up merchant who, when the mood took him, could knock out a riot of a pop tune.

The last time I saw The Fall was not what turned out to be Smith’s final appearance in public in Glasgow. This is something I now deeply regret, and have only seen various clips of on YouTube. My final Fall experience was at what turned out to be the last ever All Tomorrow’s Parties festival at Pontins holiday camp in Prestatyn, North Wales. Curated by Stewart Lee, the weekend brought together several generations of off-kilter music in Pontins’ gloriously archaic fun palace of dance halls, bars and amusement arcades, with chalets provided so no-one needs to rush off after last orders.

The Fall were scheduled to play early on Saturday night on the main stage, with John Cale head-lining. Due to the promoters behind the event effectively going bust, Cale cancelled. This meant that The Fall were re-scheduled to play later, leaving a lot of drinking time for anyone who fancied getting hammered.

As it turned out, Smith was as fine as he’s ever been over the last few years, barking and gurgling his way through a set drawn largely from 2015 album, Sub-Lingual Tablet. Up until that point Smith and co attracted the biggest crowd of the weekend. Many of these were perhaps seeing The Fall for the first time, maybe curious about the mythology about the band that they’d picked up second-hand.

Watching what, for me at least, was a relatively incident-free set, I wondered whether any of the younger members of the audience were having a similar sort of epiphany I’d experienced thirty-six years before. In truth, a lot of them looked slightly bewildered. Maybe they were just trying to be cool, and were in fact having internal palpitations as they tried to decipher what this crazed, ancient-looking gargoyle was even doing up there.

When, after six songs, Smith abruptly turned down the amps and marched the band offstage, presumably for some kind of pep talk, I wondered what they thought then. This wasn’t what the frontman of a pop group – not even a post-punk pop group – was supposed to do, and it’s unlikely they’d seen anything like it onstage before. When the band returned for a blistering rattle through Theme from Sparta FC, however, all was well again, even if Smith did finish the set from behind a curtain.

For me, however, the fun was just beginning. I bumped into my mate John, and he wasn’t happy. John had his own epiphany that weekend when he discovered a hitherto untapped love of free jazz. As for The Fall, alas, he wasn’t having any of it.“That was one of the worst gigs I’ve ever seen in my life,” he said. “That’s it. I’m never going to see The Fall again. It was terrible.” And so on. I took a deep breath. I’d been waiting for this. “But John,” I said. “It’s not terrible at all. It’s a perfect example of social engineering on a par with the avant-garde Polish theatre director, Tadeusz Kantor.”

To be fair, given that we’d been drinking over-priced lager in plastic glasses for several hours, it was a bit of an arsey thing to say, but the fact that it made John even angrier kind of proved my point. I like to think so, anyway, although he might well have been right. No matter. Charlotte Church’s Late Night Pop Dungeon was about to start next door. That calmed us down, and all was well with the world.

When I think of seeing The Fall play live over the last few years in all Smith’s erratic glory, I think of Brian Friel’s play, Faith Healer. I only made the connection the last time I saw the play done in a production at the Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh. I was taken aback by how much this devastating meditation on life, death and belief of self as much as anything else seemed to reflect the assorted rise and falls of the band’s self-styled hip priest.

Like several of Friel’s plays, Faith Healer is structured over a series of monologues played straight out to the audience. There are four linked pieces in Faith Healer, spoken by the play’s three characters. Grace and Teddy are the wife and manager respectively of Francis Hardy, a travelling faith healer who’s lost his touch. Francis, who has the first and last monologue, is a charismatic showman, who, when his gift works, is able to heal as many as ten people in one village. When the gift fails him, there’s nothing he can do but move on to the next town, unable to stop himself from plying his wares despite being a shadow of his former glory.

The comparisons here with any showbiz act are obvious. This is the case whether it’s a comedian slogging their way around the clubs, or a band touring the spit-and-sawdust toilet circuit in a hired van. When I saw Faith Healer at the Lyceum, though, for some reason it seemed specific to Smith and The Fall. This was as much to the transcendent, transformative power of those early, era-defining shows as it was to the later ones that threatened to and sometimes did fall apart, be it through illness, drink or indifference. Sometimes, as with Francis, so it was with Mark E Smith and The Fall. Some nights there were no miracles, and no-one was saved.

Watching Faith Healer, I imagined a production in which Smith starred as Francis. Teddy would be played by Alan Wise. The role of Grace would be split between each of Smith’s ex-wives and girlfriends.

As key members of The Fall at various points as well as being wife’s numbers 1 and 3 respectively, Brix and Elena would be the obvious choices. There would be room too for Saffron Prior, who ran The Fall’s fan club before becoming wife number 2. And maybe we could get Kay Carroll, the group’s ferocious former manager, who did all of Smith’s dirty work in the early days, and in dealing with the business side of things took no prisoners. Or maybe she could play a female Teddy?

Either way, I reckon it would’ve worked well, this production of a play in which no-one knows when to stop doing what they do, because if they did, even after everything goes wrong, their entire world would crumble. So, like Francis, they carry on regardless, even if it kills them.

I’m not sure what my earnest teenage self would make of all that, but then, earnest teenagers know everything about everything. That was certainly the case in another late night ‘review’ penned by the now eighteen-year-old me in the small hours of Saturday December 4th 1982 after another Fall gig – my fifth – at the Warehouse on the Friday.

‘…it’s reassuring to know that in these days of recession-ridden pop banality there’s one band who don’t let up. If the apocalypse were to happen tomorrow The Fall would be dancing on our graves, laughing at the crap beneath them.’

I hope Mark E Smith’s laughing his head off right now.