Decades

When I saw Joy Division play live, it felt like they were the most important band on earth. Here they were, these four lads from Manchester or thereabouts, who’d transcended punk and turned it into something far darker. Their album, Unknown Pleasures, felt like the soundtrack to some dystopian apocalypse. The record was a masterpiece of terrifying beauty, and Joy Division were soothsayers of an even scarier future. On the fortieth anniversary of the death of the band’s mercurial singer Ian Curtis, and almost four decades since the release of the band’s second and final album, Closer, the rest of the world seems to think so too. This is clear from the forthcoming re-press in July of Closer on crystal clear vinyl. Remastered versions of the band’s singles, Transmission, Love Will Tear Us Apart and Atmosphere, will be released on 12-inch vinyl simultaneously. These follow on from the 2019 commemorative edition of Joy Division’s debut album, Unknown Pleasures. Both acknowledge the band’s importance as artists, and the records as works of art, from the ornate Peter Saville-designed sleeves to the stunning music captured within.

Amidst the deserved flurry of tributes, this weekend sees the anniversary of Curtis’ death marked by Moving Through the Silence – Celebrating the Life and Legacy of Ian Curtis. This online event is hosted by Headstock music and mental wellbeing festival, and brings together Bernard Sumner and Stephen Morris of Joy Division and New Order in conversation with writer and former Hacienda DJ Dave Haslam to raise funds for mental health charities.

With the date of Curtis’ death, May 18th, marking the start of Mental Health Awareness Week, also taking part in the two-hour event will be Brandon Flowers of The Killers, Elbow, Lonelady and Maxine Peake, with other participants to be announced.

Like Tiny Changes, the charity set up following the suicide of Frightened Rabbit singer Scott Hutchison in 2018, Moving Through the Silence highlights an awareness of everyday mental health issues that were barely acknowledged during Curtis’ lifetime.

As well as the Moving Through the Silence event, the anniversary is also marked by the limited release of So This is Permanent, a film of a 2015 concert by former Joy Division and New Order bassist Peter Hook and his band The Light. The show took place in a church in Macclesfield, the town where Curtis was born. Hook and co played a three-hour show that went through Joy Division’s entire back catalogue, and this will be the first time any footage of it has been seen. Streamed on Facebook and YouTube, So This is Permanent is available for twenty-four hours from Monday May 18th at noon.

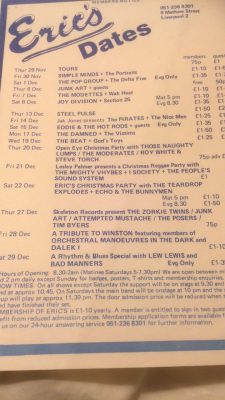

Such justified attention is a long way from when I saw Joy Division, which was roughly somewhere between 5pm and 7.30pm on Saturday December 8th1979, in a club called Eric’s in Liverpool. Back then, if you mentioned the phrase Joy Division to most people beyond the four walls of the arts lab masquerading as a city centre basement dive that was Eric’s, likely as not they’d look at you funny, not knowing what you were on about.

Joy Division were never a big band. When I say big, I mean how ABBA were big, or The Police and Blondie were. While the latter two were born out of pre-punk in much the same way as Joy Division, they crossed over into the mainstream in a way that the latter never did during their lifetime. That’s unless you count Love Will Tear Us Apart posthumously making it to a lucky number 13 in the charts. The cheap and not terribly cheerful video for the song premiered on Saturday morning kids’ TV, before it dropped out of view, having made its point as one of the greatest pop songs ever put on record.

Part of the difference was something to do with Blondie and The Police being on major labels, while Joy Division remained signed (or not) to the defiantly Manchester-based Factory Records. But Joy Division were never big in the way we think they are now. How could they be? In their three-year existence as a working band, following their self-released An Ideal for Living EP, they made two albums – Unknown Pleasures and Closer. There were a couple of singles – Transmission and Love Will Tear Us Apart – plus the free flexidisc of Komakino released alongside the latter. Inbetween came the uber-rare 7” of Atmosphere and Dead Souls, released on the French label, Sordide Sentimental, in an edition of 1,578. The record’s collective title, Licht und Blindheit, spoke volumes.

Joy Division’s first release on Factory was on one side of their record label’s hard-to-find double seven-inch Factory Sample compilation, while a couple of Unknown Pleasures off-cuts appeared on Edinburgh label Fast Product’s Earcom 2 twelve-inch. Like Love Will Tear Us Apart, Joy Division’s second album, Closer, was released posthumously. As was a 12” of Atmosphere and a new recording of a track from Unknown Pleasures, She’s Lost Control.

Live too, Joy Division weren’t exactly stadium-fillers. The biggest venues they played were on the university and concert hall circuit supporting Buzzcocks on a 25-date tour in the autumn of 1979. This opened at the Mountford Hall in Liverpool and finished up at the Rainbow in London. These were venues of a size, and exposed the band to a bigger audience. But, as support act, Joy Division were still playing second fiddle, however much some who witnessed them reckoned they blew the main act offstage.

Other than that, Joy Division mainly played clubs; The Factory in Manchester (of course), Eric’s in Liverpool, and numerous others on the nascent independent circuit that had co-opted beat band cellars, neon-lined discos and chicken-in-a-basket gaffs in their own image. As Dave Haslam pointed out on social media, what turned out to be Joy Division’s last ever gig on May 2nd1980 saw them play the dining hall of a Birmingham University hall of residence to an audience of 300. They were due to play Eric’s again the next night, but the show was cancelled due to Curtis being too ill to perform after being carried offstage the night before.

Yet, for some of us, by the time they ended so abruptly and so tragically, Joy Division were already the biggest band in the world. In the parallel universe opened up by the music papers, John Peel and, if you lived in north-west England, Tony Wilson’s Granada TV arts magazine show, What’s On, the possibilities seemed infinite.

Wilson got Joy Division on teatime news show, Granada Reports, doing Shadowplay. He also put them on What’s On, performing She’s Lost Control. They played that again along with Transmission on BBC2 youth programme, Something Else. These were Joy Division’s only TV appearances during the band’s lifetime, and in those days, when Top of the Pops and The Old Grey Whistle Test were all that was on offer, were something to cherish.

Even so, for every young shaver in search of enlightenment who had their world turned upside down while watching, another ten would have switched over to the other side. The fact remains, in most people’s eyes, if they’d even heard of them, Joy Division weren’t that big at all.

So, when the fortieth anniversary of Unknown Pleasures, was marked in 2019 with a wave of profile-raising activity to accompany it, I decided to ignore it all, even the ten short films inspired by each track, and made by directors who included Lynne Ramsay. There had been more than enough books about Joy Division, I reckoned, which both documented and mythologised the band. One of the earliest of these dates right back to 1984, when Mark Johnson’s book, An Ideal for Living: An History of Joy Division was published.

With input by Paul Morley and others, this now relatively hard to find tome came into public view when it was reviewed on a TV show called Eight Days A Week, hosted by journalist Robin Denselow. The panel was made up of Wham! singer George Michael, Smiths figurehead Morrissey, and Radio 1 DJ Tony Blackburn.

While Blackburn and Morrissey were by turns disparaging and waspishly evasive about the merits of both the book and its subject, it was Michael who declared himself a Joy Division fan, claiming Closer as one of his favourite records. In a world where the gulf between commercial chart pop and indie so-called integrity was still vast, this was a surprise to many.

Since then, there have been autobiographies by Peter Hook and Bernard Sumner, Joy Division and then New Order’s now estranged bass player and guitarist. Most recently, there was Record Play Pause, the first volume of memoirs by drummer Stephen Morris. Morris was always the most forthcoming one in the band. A mate who saw him read at a literary festival in London said he reminded him of Alan Bennett. That sounds great, and if I eventually give way, I’ll probably pick Morris’ book.

I’ve already read some of the eyewitness accounts. Touching from a Distance was by Curtis’ widow, Deborah Curtis. There was one by Wilson, and other by John the Baptist-like journalists like Mick Middles, Jon Savage, and, especially, Paul Morley. Each book has a story to tell, filling in the jigsaw of Curtis’ life as they go.

Curtis and Joy Division have been immortalised onscreen too. This happened first in Michael Winterbottom’s Carry on up Factory Records styled 24 Hour Party People, then in Control, directed by photographer Anton Corbijn.

All this attention is great on one level. It means Joy Division have been recognised as the major artists they were, a fact now recognised globally. It’s vindication too for those of us who put our faith in them at a tender age, and made them our new – messiahs, was it? But none of that matters now. All the myths are already out there. What else could anyone possibly have to say about Joy Division that hasn’t already been said?

Then there were the corporate cash-ins that now go hand in hand with the rock heritage industry. Punk was supposed to have done away with all that, but money talks, and corpses are devoured.

Unknown Pleasures t-shirts with the Peter Saville designed white-on-black image of radio waves from the CP 1919 pulsar lifted from the Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Astronomy have long been available in high street stores. Edinburgh’s tellingly named second-hand record shop, Unknown Pleasures, has one in its window, permanently nestled next to a Trainspotting t-shirt. These are both presumably best-sellers positioned in order to attract any pop-culturally savvy tourist’s eye as they pass by.

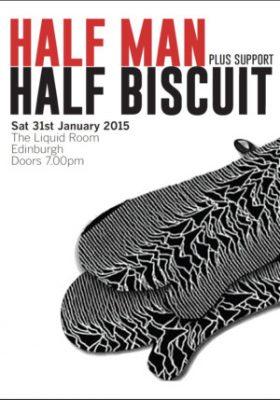

The image is ubiquitous now, not just on t-shirts, but moulded into limited edition training shoes and a clothing line initiated by Saville with menswear designer, Raf Simons. Then there is the inevitable appearance of Joy Division oven gloves, a range inspired by the song, Joy Division Oven Gloves, which appeared on Merseyside absurdists Half Man Half Biscuit’s even more magnificently named 2005 album, Achtung Bono. Half Man Half Biscuit’s own cult career was championed by John Peel, and they’ve never been shy of squaring up to sacred cows with acerbic intent.

Of course, a little irreverence is always a good thing. Just ask Peter Hook, who, between 1993 and 1995, fronted Hooky and the Boys, the house band across two series of his then wife Caroline Aherne’s chat show spoof, The Mrs Merton Show. For Hook, who had gone full metal racket with his New Order side project, Revenge, this was quite the leap into showbiz, albeit of a knowingly post-modern kind.

Such prime-time TV fun arguably helped pave the way for Let’s Dance to Joy Division, a hit single in 2007 for Liverpool band, The Wombats. This student-union friendly smash was sired following an incident in Liverpool scene hang-out, Le Bateau, when Wombats singer Matthew Murphy and his girlfriend danced on a table with drunken abandon to Love Will Tear Us Apart.

Murphy and partner’s impromptu wig-out was a perfect illustration of how Joy Division have become part of some loose-knit post-punk indie-disco canon. Murphy and his peers of 2007 and the generation that has followed are likely to look on Joy Division in much the same way as my generation did with The Doors or the Velvet Underground. Touching from a distance, if you will, except with dance moves to go with it.

The first time I saw people dancing to Joy Division in a club I was shocked and delighted. I’m not talking about the way people used to dance to Joy Division forty years ago, when they’d do bad imitations of Ian Curtis’ dying fly routine. This was much later, at a post-millennium Edinburgh post-punk club night called Gulag Beat.

It was the opening guitar shards of Disorder that caught my ear the night I first witnessed it. I’d probably not heard the opening track from Unknown Pleasures for years, but for it to be blasted through night-club speakers immediately grabbed my attention. Gulag Beat’s Thursday night regulars filled the club’s tiny basement dancefloor to dance, dance, dance with art school abandon and no discernible sense of historical context to weigh them down. This spontaneous communal spectacle was reinventing and reimaging a song that had clearly evolved into something else from when Joy Division played it live, and no-one in the audience moved a muscle.

As the song gathered momentum to Curtis’ lines about how lights were flashing and cars were crashing, so too did those on the floor. By the end, as with the best dance music, the exhilaration of release had become a thrashing physical thing. The name of the song, Disorder, and of Unknown Pleasures itself, suddenly made sense with a renewed vigour, so it was like hearing it for the first time. But before anyone could pause for breath to take in what had just happened, Disorder segued into Deceptacon by Le Tigre, and the moment passed.

A couple of years after Half Man Half Biscuit and the Wombats, Hook began touring as Peter Hook and The Light. Now no longer part of New Order since they reformed without him, Hook’s new band played Unknown Pleasures and then Closer in full. Over the next few years, Hook and The Light gradually made their way through New Order’s back catalogue as well. Which is fair enough. They were his songs too.

In 2011, Joy Division’s briefly reconstituted Manchester post-punk contemporaries, Magazine, got in on the act. On their first new album for thirty years, a song called Hello, Mr Curtis (With Apologies), found vocalist Howard Devoto declaring that, unlike Curtis and Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, who shot himself in 1994, he categorically won’t be committing suicide. Instead, like Elvis Presley, he would rather die on the toilet.

Three decades after Curtis’ passing put a dramatic full stop on Joy Division, only now could such blackly comedic existential ruminations come out into the open. Every generation needs their martyrs to mourn. My mum and my sister got theirs within a few weeks of each other in 1977. Not long after Elvis left the building for good aged 42, Marc Bolan of T-Rex died in the passenger seat of a purple mini that crashed into an oak tree. I had to wait almost another three years for my chance to grieve by proxy.

But when John Peel announced Curtis’ death on his programme before playing New Dawn Fades, I lapped it up. Here was a teenage rites of passage moment to call my own, amplified in print in the same music papers where I’d first read about Joy Division. Rather than the grainy pictures of a year earlier, now there were front page headlines, monumental looking full-page portrait shots and lengthy eulogies.

The NME put an image of Curtis on the front cover in a way that gave him the gravitas of a tortured artist. In Sounds, Dave McCullough wrote an emotive full-page outpouring under the headline ‘The short goodbye…’, with the sub-heading, ‘The last Joy Division feature’. The article closed with the lines ‘That man cared for you, that man died for you, that man saw the madness in your area.’ The much-mocked sentence referenced two songs by The Fall. In the first, That Man, Mark E Smith lacerated the idea of false idols destined to disappoint. The second, In My Area, was the B-side of the band’s 1979 single, Rowche Rumble.

Both songs appeared on The Fall’s Totale’s Turns (It’s Now or Never) album, released just over two weeks before Curtis’ death when he’d hung himself after watching Werner Herzog’s film, Stroszek, on BBC 2’s Saturday night foreign film strand. I’d watched it as well the same night, happy in my own teenage bubble, not foreseeing how the film, which ended with the implication that its street entertainer hero shot himself, would become associated with Curtis’ death. It was a strange way for McCullough to end his article, and in terms of wearing grief on his sleeve, seemed to cross a line. Mark E. Smith apparently wasn’t happy either.

And then there was the brother of my sister’s mate who lived at the end of our street, who I’d see around at gigs a couple of years later, though never spoke to him. He was slightly older, though I noticed he’d started wearing a serious-young-man overcoat, the same as me. One of his favourite TV programmes was M*A*S*H, the American Korean War set comedy drama series, which my sister used to go round to watch at their house because we didn’t have BBC2. And when it somehow trickled along the street that he’d killed himself, everyone mentioned that the theme song of M*A*S*H* was Suicide is Painless.

Beyond all this grown-up stuff, I got to thinking, about how much Joy Division mattered to me back when I was a sulky teen, and even though I hardly listen to them at all these days, how much they probably still do. I got to thinking as well that maybe it’s my problem, and how there’s nothing really wrong with all these books and radio programmes and fortieth anniversary commemorations.

Maybe I’d prefer it if Joy Division hadn’t become a big band like ABBA. Now they’re getting all this attention, ushered into being most likely, by people my age who now hold positions of power in publishing and radio, maybe I resent it somehow. Maybe a part of that sulky teen for whom Joy Division mattered so much still thinks they’re his secret, and his alone. Except, they were a lot of other people’s secret as well.

Because, outwith the perceived doom, gloom and hand-me-down existentialism picked up from Ballard and Burroughs, Joy Division had a common touch. They weren’t a student band. Not at first, anyway. It was the scallies who picked up on Joy Division first, perhaps recognising something of their own working-class lives in the yearning of the music that suggested those lives could be transcended.

As with many bands of that time, I read about Joy Division before I ever heard them. That was by way of reviews of Unknown Pleasures in Sounds and NME. It was Dave McCullough’s 5-star appraisal in Sounds I read first in the issue dated July 14th, 1979.Beneath a headline that said ‘Death Disco’ was a grainy picture of the band, with the lens looking up at them. In the picture, they were standing like a quartet of civil servants on their lunch break before the curve of a very Manchester looking building towering above them. Given that the album had been released a month earlier on June 15th, the review seemed rather late, but I was none the wiser.

I’d not been buying the music papers long, but the review was like nothing I’d ever read before. It was more like a short story than anything. It was about someone called Andrew, who listens to Unknown Pleasures alone in his room, surrounded by a mess of his own making, with hints of something unspeakable having happened. It was like the beginnings of a bedsit-land update of Metamorphosis, Franz Kafka’s story about a young man who transforms into a giant insect.

McCullough’s review mentioned all the songs on the album except New Dawn Fades. He referred to something called The Waiting Room, which seemed to be another title for I Remember Nothing. He also mentioned Doors singer Jim Morrison, whose name was being dropped all over the music papers that summer. For all the mystery the review evoked, I knew exactly what Unknown Pleasures sounded like.

I was fourteen years old and was in the throes of a very private Damascene conversion which had quietly begun a couple of years before by way of punk, or my idea of punk by way of what I’d read and heard. I’d moved quickly, from the first Stranglers LP, Rattus Norvegicus, to Buzzcocks and Magazine. I’d not even realised the connection between those last two until Tony Wilson did his half-hour documentary, B’dum B’dum, on Pete Shelley and Howard Devoto as part of a series of Thursday night What’s On specials. The film is now out there on YouTube and is worth every second of Shelley/Devoto chat.

There was a lot I lapped up, but there was even more I missed, ignored, didn’t get, or just didn’t get to hear. Apart from anything else, I didn’t know where or how you could find all this stuff I was reading about. I was also just that crucial bit too young to go out and hear it live for myself.

Despite all this, it was clear that Joy Division could be my band. Even reading about them while looking at that grainy photograph above the Sounds review made my stomach churn. So, when I heard Day of the Lords from Unknown Pleasures on John Peel, everything clicked.

Here was something which seemed much weightier than mere pop music, driven by a slow-motion sense of claustrophobic foreboding concerning some unnamed oppressive force. The song’s key line, ‘Where will it end?’ was repeated by Curtis with a mixture of desperation and resignation at the fact that we were all doomed. It was perfect.

I didn’t buy Unknown Pleasures straight away after reading about it in Sounds. It was too soon to make the leap, somehow. Before the year was out, I’d be rummaging through the racks in Probe, Liverpool’s in-crowd record shop, looking for hidden musical treasure as the smell of patchouli oil wafted by. Pocket money was too tight to mention, and while buying singles had been a regular occurrence since I was a kid, taking the plunge with an album was a Big Deal.

On Saturday mornings I’d got into the habit of going into town with two schoolmates, Faza and Turner, to buy records. We’d get the bus, then split up and do our own thing before meeting up again to get the bus home and show off our booty. For some reason, rather than going to Probe, I went to Virgin in St John’s Precinct, where Unknown Pleasures was on sale for £2.99.

I looked at the the outer sleeve held captive inside its shrink-wrapped cellophane. At its centre, its heavy-set pitch-black square was broken only by a rectangle of white wavy lines. The image looked like an approximation of some miniature mountain range from some far-off continent that would have been hidden in the dead of night if it wasn’t for the icy ebb and flow of its own topography. Only later would I discover it was actually a reproduction of the aforementioned pulsar CP 1919, originally created by radio astronomer Harold Craft in 1970 to help illustrate how smaller pulses could exist within larger ones.

On the back of the record, book-ending the same central area as the front, was the title of the band and the record at the top. At the bottom was its catalogue number and acknowledgement that it was ‘A Factory Records Product’. Both were in tiny white letters in the most formal of fonts, with only black space between. There was no track listing, no names of who was in the band, let alone any pictures of them, and no clues about where it might have been recorded or who played what.

Record covers I’d grown up with had photographs of the band whose record it was striking a pose of one sort or another. Whatever the image, it threw out an invitation for the potential listener to step into its world. Unknown Pleasures seemed to do the opposite, or so I thought. The cover was making a statement, alright, but it was one that wilfully set itself apart, hiding in plain sight from the crowd who would soon claim it for their own. It seemed to give voice to some intangible sense of… what? Alienation? Otherness? Angst? I didn’t have a clue.

It was this not knowing what was going on with this mysterious piece of black plastic that I’d just bought that made it both so shocking and enticing. Not shocking in a PVC, punk rock, swearing-on-the-telly and gobbing at the audience kind of way. Quite the reverse. What was going on in here was anti-social in a much more insular and awkward kind of way. As the music contained within would prove just as much as history eventually did, Unknown Pleasures wasn’t a cry for attention. It was a cry for help.

Here was a mysterious world of potential possibilities that I wanted to know about, however much it might mess me up in the process. Even better, it was right here in a record shop in a busy Liverpool shopping precinct on a Saturday afternoon, while everybody else was buying shoes and other things that didn’t matter.

But I couldn’t tell Faza and Turner any of this when I met up with them again and we went for the bus home. Record shop plastic bags in hand, we were desperate to show off our purchases. Faza had got a Blondie album, either Parallel Lines or Eat to the Beat. Turner had got either Outlandos d’Amour or Regatta de Blanc by The Police. Both Parallel Lines and Outlandos d’Amour were released in 1978. If it was those two, then Faza and Turner were really late to the party. Eat to the Beat and Regatta de Blanc came out within a couple of weeks of each other in October 1979. If Faza and Turner had spent their pocket money on the latest releases, then it was me who was trailing.

Was I really that late? If so, Message in a Bottle by The Police will have been in the charts, and Dreaming, which was the first single from Eat to the Beat, will also have been out. Joy Division’s single, Transmission, was also released that October. Did I buy it on the same day as I got Unknown Pleasures? They’d played Transmission and She’s Lost Control on Something Else in September, so I certainly would have heard it. I will have also been aware of them supporting Buzzcocks at Liverpool University’s Mountford Hall on October 2nd, though for some reason hadn’t taken the leap to make it my first ever paid-in gig, even though I’d thought about it.

But now there we were, Faza, Turner and me, on the bus home. Faza and Turner showed off their Blondie and Police albums, which both had big pictures of the bands on the cover. I pulled out Unknown Pleasures, which seemed to revel in its own blackness, giving nothing away. Faza and Turner looked at it with disdain.

“What’s that?” one of them snarled. “Where are the song titles?” asked the other? “They’ll be on the inside cover,” I said confidently, and proceeded to dig my fingernails into the cellophane to rip it off and open it out to the world with pride. On doing so, all I saw of the inside cover was a white background on which was a black and white photograph of a half open door at the end of a hallway. The door was shrouded in shadow, with a hand reached out to the doorknob from the room within. Puzzled, I pulled out the record itself, thinking the song-titles would be on the label.

As it was, the image that I’d mistaken for a mountain range from the front cover was reproduced. On one side, there were white lines on a black background as with the outer sleeve. On the other, black lines were on white. Rather than song titles, the only words again were the band name and the album title, with the word ‘Inside’ on one side, and ‘Outside’ on the other.

I reeled at this lack of obvious information, quickly putting the record back in its bag. Faza and Turner held on to their own objects of affection, laughing at me. Stylised images of Debbie Harry and Sting now seemed to mock my out-of-depth befuddlement. Bloody Factory. Bloody Joy Division. It was only when I got home and played it that I finally saw the track listing on the other side of the record’s inner sleeve.

And what titles. I knew She’s Lost Control and Day of the Lords, but the rest were as stark and as stiff as everything else on the record. Disorder. Candidate. Insight. Shadowplay. Wilderness. Interzone. Stark one-word titles that read like chapters from a science-fiction novel. The other titles that ended each side hinted at something bigger and more disturbing. New Dawn Fades said one; I Remember Nothing went the other.

Whatever was going on here, I knew this was a world I wanted to get lost in before I’d heard a note of it. Only much, much later did I find out that the photograph of the door on the inside cover was an image called Hand Through a Door, taken by American photographer Ralph Gibson. Me and Peter Saville both.

I only ever saw Joy Division once. That I saw them at all is something I like to use as a trump card in all those ‘what was your first gig?’ conversations middle-aged men like to have in the pub. Except, if I’m honest, Joy Division at Eric’s under 18s matinee on December 8th1979 wasn’t really my first gig at all. It was my first indoor gig in a proper club venue, however, if you can call Eric’s proper, so I reckon it still counts.

My first actual gig was an open-air Rock Against Racism festival in Walton Hall Park the year before. On the bill were a bunch of local bands I’d never heard of, including The Spivs, The Nancy Boys, 29thand Dearborn and Kilikuri. The day was headlined by Ded Byrds, and also featured a feminist cabaret troupe called The Sadista Sisters and radical rock theatre company Belt and Braces.

A couple of months before I saw Joy Division I’d also been to another open-air festival in Walton Hall Park, where I saw a band called The Moderates for the first time. It was a Campaign Against Youth Unemployment gig, but hardly anyone came, not even the headline act, which was supposed to be The Passage. John Brady, the male singer in The Moderates, somewhat waggishly suggested that hardly anyone was there because they’d all found jobs. And who goes to open-air gigs in October,anyway?

I didn’t realise it then, but there were links to Joy Division all over. This was especially the case at the first Walton Hall Park gig, where there were connections as well to much bigger bands. The open-air afternoon gig also gave me a taste of old-school counter-cultural activity. Some of it would not very much later be dubbed alternative cabaret and gave me an inkling of how different artforms are all mixed up together. But this was my first ever gig, and I didn’t really care about all that. I was all about the bands.

Ded Byrds were a band formed by a guy called David Knopov, and another guy called Ambrose Reynolds, who had both been in a band called the O’Boogie Brothers. The O’Boogie Brothers also featured Ian Broudie and Nathan McGough, and they supported Deaf School at Eric’s before splitting up at some point in 1977.

While Broudie would join Big in Japan and McGough would eventually manage Happy Mondays throughout their wild days on Factory Records, Knopov and Reynolds formed Ded Byrds, who are described on Wikipedia and probably other places besides as ‘cabaret punk’. After a couple of years, Seymour Stein signed them to Sire Records for a five-album deal on the proviso they changed their name, so they became Walkie Talkies. I remember there being some banter about it onstage at Walton Hall Park from whoever was compering, something about ‘wivvy spivvies’ relating to The Spivs, and ‘wankie tankies’ or something. Whatever happened, they were still Ded Byrds when they played Eric’s later that year, opening for Joy Division and John Cooper Clarke that November.

As is the way of these things, only one single was ever released by Walkie Talkies before they split up. Ambrose Reynolds went on to join Nightmares in Wax with local Liverpool legend Pete Burns, then joined Jayne Casey from Big in Japan in Pink Industry. Reynolds produced Liverpool’s lesser-known Factory act, The Royal Family and The Poor, and worked with Holly Johnson as part of an early line-up of Frankie Goes to Hollywood.

Such were the six or less degrees of separation in Liverpool’s music scene at the time, though there were greater glories to come, especially for Ded Byrds’ guitarist Wayne Hussey and drummer Jon Moss. Hussey joined Burns in Dead or Alive, then went on to join Sisters of Mercy before forming The Mission. These really were big bands.

The Sadista Sisters, meanwhile, categorically weren’t the inspiration for Rock Follies, the Howard Schuman scripted BAFTA-winning 1976 TV drama about a girl group trying to make it in a man’s world, but they could have been. The actual inspiration came from Rock Bottom, a trio formed by actress Annabel Leventon with friends Gaye Brown and Diane Langton. Having pitched the idea to Thames Television with Schuman, Rock Follies was made without their input, with different actresses cast as the band. Leventon took Thames to the High Court in 1982, and the company was found in breach of confidence in using Leventon and co’s idea and screening the two series of Rock Follies. Leventon, Brown and Langton were subsequently awarded substantial damages.

As it was, Rock Follies starred a pre-Don’t Cry for Me Argentina Julie Covington, Rula Lenska and Charlotte Cornwell as Dee, Q and Anna, aka The Little Ladies. While the lyrics for the songs sung by the trio were penned by Schuman, the music was composed by Roxy Music saxophonist and oboist, Andy Mackay.

By this time, Roxy Music were five albums into an ever-changing career that was in the throes of morphing from pop-savvy glam-art-rock into post-modern lounge-core sophisti-pop. By the time of the band’s 1978 album, Manifesto, released after a two-year hiatus, the transformation was a long way from the out-there urgency and aspirational ennui of the first Roxy Music album. Amongst the record’s art-school stylings, Roxy Music had a credibility that enabled them to survive the punk clear-out and influence the new generation who had grown up with their records. In terms of Joy Division, the roots of New Dawn Fades can clearly be heard in the second half of Roxy’s If There if There is Something.

Mackay’s songs for Rock Follies took things back to basics, just as the low-budget drama resembled a no-frills fringe theatre production. In 1976, the Rock Follies soundtrack album went to number 1. It was a review of Rock Follies in London listings magazine, Time Out, headlined ‘It’s the Buzz, Cock!’ that inadvertently gifted Messrs Devoto and Shelley the name of their nascent punk pop combo. After promoting and supporting the Sex Pistols at the legendary Lesser Free Trade Hall shows in Manchester, Buzzcocks made their recorded debut in 1977 with their Spiral Scratch EP, produced by Martin Hannett, credited as Martin Zero.

Also on the Walton Hall Park RAR bill, The Belt and Braces Roadshow were another agitprop theatre troupe, co-founded by Gavin Richards. Within a couple of years, the company would have a hit with Richards’ version of Dario Fo’s radical farce, Accidental Death of an Anarchist. Prior to this, Belt and Braces self-released two albums and a single. The first of these, the eponymously named Belt & Braces Roadshow Band, was released in 1975, and was produced by a pre-punk Martin Hannett.

There is little in the sound of both the Belt & Braces LP and Spiral Scratch to point towards the expansive sonic sculpture of Hannett’s work with Joy Division. There wasn’t much sign of it either at Eric’s, which, while retaining the propulsive urgency of the record, was a loud and messy affair, in which Joy Division somewhat shockingly seemed to border on Metal.

I don’t know when I decided to go and see Joy Division at Eric’s. I’d been aware of the club for a while and picked up their gig listings flyers in Probe. On Saturdays they did under eighteens teatime matinees with the same bands who played the main shows at night in normal club hours. Looking back at my old Eric’s flyers now and seeing who played, I don’t know why I only ever went once. Lack of pocket money again, probably, but I’m glad I took the leap with Joy Division.

I’d be lying if I said I remembered everything about the gig. In truth, I more remember the sense of nervous anticipation as I walked down the stairs in my cagoule, shapeless jeans, bad haircut and specs to such an already hallowed place, that had previously been off limits. I was on my own, and had been warned that anything might happen here. I hoped it would.

It was December, and according to what I’ve just looked up, the sun set at 3.53pm that day, so it will have already been dark by the time the doors opened at five. Once I paid my £1.35 admission fee (members £1.10), I remember the walls inside being a mix of red and black, with the Eric’s logo I knew from the flyers and from excerpts from an Elvis Costello gig on Tony Wilson’s So it Goes programme at the back of the stage.

I was surprised it wasn’t busier than it was. I presumed all gigs were all full all the time, like the ones they showed on the Old Grey Whistle Test and Rock Goes to College, but this was half empty. Joy Division were what I considered to be the most important band on earth, so where was everyone? I had a lot to learn. I remember moving down to the front to wait for the bands as a few other people were doing, carefully keeping my distance. Not knowing any better, I stood right beside the speakers, that were so close the pre-show reggae booming out of them made my ears tingle.

Section 25 played first. They were an austere trio from Blackpool who I’d see again supporting New Order, always the bridesmaids. They had their own brand of bass-heavy bleakness and would later go on to be hailed as pre-techno pioneers for their Looking from a Hilltop single. I would later buy their Girls Don’t Count and Charnel Ground singles, both suitably difficult records as seemingly in keeping with the presumed Factory ethos.

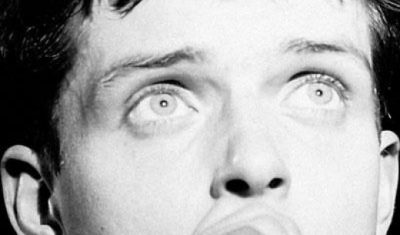

And then, Joy Division wandered onstage without a word. There’s something thrilling about seeing people in the flesh that you’ve only ever previously seen in pictures. Given that the music papers generally only ran black and white pictures, seeing Ian Curtis and the rest of Joy Division in living, flesh-and-blood colour less than five feet away, and in at times frantic motion was even more exhilarating.

After only knowing them from Unknown Pleasures and Transmission, hearing them live was a shock. Gone was the cavernous depth and space of Martin Hannett’s production. In its place was something raw and raucous, that stabbed the air with an aggression that seemed to punch and kick its way out of the psychic chamber it had been locked up in.

Some songs I recognised, others I thought I did, but wasn’t sure, as they were so loud and fast and different to the record. Others still were unrecognisable, presumably brand new. According to my schoolboy notes from the time, they played nine songs, six of which I knew, plus an encore that may have been Dead Souls.

A keyboard had been placed at the front of the stage, but for the matinee, at least, remained untouched. Standing next to the speakers at the front, my ears tingled at the abstract din bleeding through them. They seemed to ring all the way home, adrenalin pumping at what I’d just witnessed. My left ear has never functioned properly since. Try talking to my left side in a crowded bar, and I will always have to navigate my way so it’s my right ear that’s trying to listen.

I had notions of trying to hide and hang around for the main evening show, but a scary bouncer briskly ushered me out before I could decide on anything resembling a plan. I caught the bus home, where I sat beside the record player, playing Unknown Pleasures and Transmission over and over and over again.

By the time Love Will Tear Us Apart and then Closer came out after Ian Curtis died, Joy Division were a much bigger deal. Both records had become accidental epitaphs to the band’s singer, but they also went some way to secure his immortality. Where the initial run of Unknown Pleasures had shifted 15,000 copies, and only made the indie charts, by the end of 1982, Closer had sold 250,000, and made it to number 6 in the UK album charts.

Within eight months of Joy Division ending, I’d tidied myself up a bit in an army surplus store kind of way, and was down the front of Mr Pickwick’s semi-circular dancefloor watching New Order begin to change the musical landscape forever. It was their seventh or eighth gig under that name, and they appeared with a new keyboardist, Gillian Gilbert. It was January 1981, and, after seeing a handful of gigs throughout 1980 – Magazine, The Fall, The Human League, Echo and the Bunnymen, Teardrop Explodes – I was about to embrace the nightlife in earnest.

New Order were the headline act of a new club night called Plato’s Ballroom, which aimed to bring art out of the galleries while at the same time making gigs into events a lot more interesting than the back room of a pub. As well as Section 25 and a third band, Send No Flowers, supporting, there was performance art. A guy who years later I learnt was called Mick Aslin broke out of a coffin-shaped box to a backing tape of him repeating the words ‘man’ and ‘box’. There was a light show, and silent films projected while the bands played. It was the first time I’d seen Luis Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou and L’age D’or, as well as the stream of Kenneth Anger shorts shown. New Order may have been the main event, but this was Art.

The next time I saw New Order was over two nights at the State Ballroom in Liverpool in March 1983. Blue Monday had been released a fortnight earlier, and the band had already taken the great leap forward towards the future. As they played on a stage filled with unwieldy machinery en route to spear-heading the indie-dance revolution, that Saturday teatime going deaf to Joy Division in Eric’s just a few years before felt as far away then as it does now.

For reasons I can’t really fathom, I didn’t see New Order again until they played Barrowland in Glasgow on the back of their brilliant Get Ready album after reforming in 2001. By this time, they were a very big band. Hooky was still with them then, though after playing on the album, Gilbert had taken time outto look after her and Morris’s children.

Significantly, New Order had started doing Joy Division songs, including Transmission, Atmosphere and Love Will Tear Us Apart. Previously they’d always kept away from them, but now here was Barney jumping about and whooping all over Love Will Tear Us Apart with gleeful abandon. It was as if he was reclaiming his musical past in a way that accepted how much these songs meant, both to those who’d grown up with them and those who picked up on them later.

A couple of years earlier, Mogwai had done a live cover of 24 Hours, from the second side of Closer. That was when they played the small room as surprise guests at Belle and Sebastian’s Bowlie Weekender at Pontin’s holiday camp. A chic ‘60s style café bar version of Love Will Tear Us Apart had been done for one of the Nouvelle Vague compilations. And an entire album-load of Joy Division songs had been compiled on an album called Warsaw by a bunch of Polish punk bands.

But Joy Division’s legacy went way beyond music. Ian Rankin named his 1999 novel, Dead Souls, after the Joy Division song. Rankin also chose the original flipside of Dead Souls, Atmosphere, as one of his Desert Island Discs when he appeared on the BBC Radio 4 programme. When actress Jane Horrocks did the show, she chose Transmission as one of hers.

Patrick Marber named his 1997 stage play, Closer, later made into a feature film by Mike Nichols, after Joy Division’s album. Marber suggested the title of his play should have the stress on the first half of the word. This changed preconceptions of a title which had always been a double-edged sword. Where on the one hand it suggested something intimate that drew you near, on the other it marked the end of something with startling finality.

Another playwright, Sarah Kane, whose plays continue to shake up the theatre world, took her own life in 1999 aged twenty-eight. She had once said in an interview that Joy Division were her favourite band because she found their songs uplifting.

And now the fortieth anniversaries of Curtis’ death and the release of Closer are with us. A potential surge of brand-new articles and online homages will probably read a bit like this one. They’ll be written by insiders and outsiders both, all of which will attempt to offer insights into the brief but seismic collision of musical gestalt that was Joy Division.

There will be anecdotes and stories of friendship from within what was then a tiny scene. Filmmaker and frontman of The Skids, Richard Jobson, bonded with Curtis over the fact that they were both epileptic. The late Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, of Throbbing Gristle, Psychic TV and much more besides, said he spoke to Curtis on the phone on that solitary Saturday night before he killed himself, and tried to warn others about what might happen.

Meanwhile, the Joy Division rip-off industry goes on as much as the band’s musical legacy. While writing this, a sponsored ad appeared on my Facebook feed from a company selling what is presumably an unlicensed Joy Division t-shirt. Using a 1979 image of the band against an approximation of the pulsar image from Unknown Pleasures beneath a headline of the band’s name, the t-shirt proclaims it to be the band’s ‘44thANNIVERSARY 1976-2020.’ Beneath the date, the names of the four band members are listed, with a signature of each below. At the bottom of the shirt, the legend ‘THANK YOU FOR THE MEMORIES’ implies some kind of official bootleg memorial is ongoing.

If this is where we are now, one can only speculate how Joy Division’s fiftieth will be acknowledged. Maybe no-one will care anymore, or maybe they’ll be more lionised than ever. One thing for certain is that some of those who saw Joy Division won’t be around anymore to tell the tale. Those who weren’t there, on the other hand, and who might not have even heard them will be able to read about them in one of a million places before they do. And so it goes.

Forty years on, it feels like contemporaries of Curtis or those that influenced Joy Division are dropping like flies. Tony Wilson passed away more than a decade ago now, Martin Hannett nearly three times that, and Joy Division manager Rob Gretton twenty-one years last week. George Michael, The Fall’s Mark E. Smith and Pete Shelley of Buzzcocks are gone too. As is Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, and now Florian Schneider of Kraftwerk. We’re used to it now. It’s part of getting older. There are no martyrs anymore. Just heroes.

So let’s dance to Joy Division. They may not be ABBA, The Police or Blondie, but Nerina Pallott’s 2007 cover of Love Will Tear Us Apart has just made it to the soundtrack of the TV adaptation of Sally Rooney’s novel, Normal People. Poet laureate Simon Armitage just chose Atmosphere as one of his Desert Island Discs last week as well. Buy the re-releases of Closer and all the rest, and, above all, watch Moving Through the Silence. Find out why Joy Division mattered, and still matter, now they’ve hit the big time.

Main image (top right): Photo by Kevin Cummins, published by permission.

Moving Through the Silence – Celebrating the Life and Legacy of Ian Curtis takes place on May 18th between 8pm and 10pm at https://unitedwestream.co.uk/ and can also be accessed at http://www.facebook.com/UnitedWeStreamGM/.

So This is Permanent by Peter Hook and The Light will stream on Joy Division and Peter Hook and The Light’s Facebook pages, and on Joy Division’s YouTube channel from May 18that noon, and will be available for 24 hours. The stream is free, but viewers are encouraged to donate to The Epilepsy Society.

New vinyl editions of Closer, Transmission, Love Will Tear Us Apart and Atmosphere are released on July 17th.