Dance this mess around

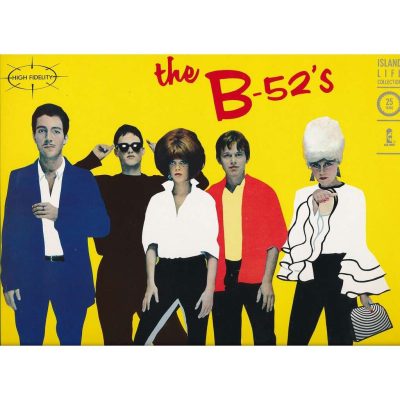

There was something about Cindy Wilson when she played at the Liquid Rooms in Edinburgh in February this year as part of a short tour. It wasn’t the way the long-time B-52s chanteuse and co-founder of the ultimate party band played the whole of her recently released solo album, Change, bolstered by a young band drafted in from Wilson’s home town of Athens, Georgia. Nor was it the way a short-haired and gamine-looking Wilson preceded her set of breathy electronic lullabies with an extended theremin solo, or the way each song segued into the next without a word to the audience. This rendered the occasion more akin to a live art performance piece tailored for a late night gallery happening than anything resembling rock and roll. Neither was it the fact that Wilson and band didn’t play one crowd-pleasing song from the B-52s joyous back-catalogue of wacky, wiggy and freaky-deaky parallel universe pop classics, on many of which she sang rip-roaring lead vocal. Nor was there a hint that this year is the fortieth anniversary of the release of both the B-52s debut single, Rock Lobster, and the original quintet’s eponymous first album, released in May 1978. This followed the band’s giddy and accidental formation a couple of years before as the playfully apostrophised B-52’s after Wilson, her brother Ricky, Fred Schneider, Kate Pierson and Keith Strickland shared cocktails at a Chinese restaurant in Athens before playing their debut gig at a party on Valentine’s Day 1977.

There was nary a hint in Wilson’s performance of the barefoot dervish on Give Me Back My Man or the countrified melancholy of Ain’t it a Shame. Nor was there a jot of the vocal gymnastics of Girl from Ipanema Goes to Greenland. Beyond all these absences in a still sublime and quietly transcendent performance, there was something else going on. That something was about Cindy Wilson’s coat.

The presumably faux leopard-skin three-quarter length coat (Wilson’s fellow B-52 Kate Pierson is a high-profile animal rights and anti-fur activist) the singer wore throughout her Edinburgh performance with a plain black ski pant ensemble looked chicly familiar. For those well versed in the excesses of the B-52s wardrobe, the band’s trashy, flashy and consciously camp retro-vintage thrift store aesthetic seemingly plundered from Fellini’s dreams are still boldly on trend. If anyone understands the dress-to-impress excesses of La Dolce Vita, it’s a B-52.

One couldn’t be sure, but the vintage winter warmer was a dead-ringer for the one Wilson wore in the video for the band’s 1989 single, Deadbeat Club. But that was almost thirty years ago. Could it be so? And how could such a garment have survived so long and remained so fresh looking? Or maybe Wilson has an entire roomful of three-quarter length faux-leopard-skin coats?

Either away, other than a twanging cover of Athens GA contemporaries Oh-Ok’s bouncy and off-kilter early ‘80s song, Brother, it was the only obvious nod to Wilson’s sartorial and musical past. The album features another cover, Things I’d Like to Say, a gorgeously smoochy ballad by 1960s psych-baroque soft rock band New Colony Six.

The B-52s always had a way with a cover, from their take on Downtown, Tony Hatch and Jackie Trent’s hymn to clubland nightlife; to another 1960s song, Paperback Writer by the Beatles. Like them, and for all the ice-cool splendour of her tellingly titled new record, the coat’s appearance spoke volumes about where Wilson came from.

Deadbeat Club was the fifth and final single from Cosmic Thing, the B-52s fifth album, released in 1989 with production gloss provided by Nile Rodgers and Don Was. The first two cuts from the record, (Shake That) Cosmic Thing and Channel Z, announced the return of the B-52s after a hiatus following the death of guitarist Ricky Wilson from AIDS-related pneumonia in 1985. This happened shortly after the band’s previous album, Bouncing Off the Satellites, had been completed.

It would be the third and fourth singles from Cosmic Thing – Love Shack and Roam – that fully launched the B-52s into the pop stratosphere. Love Shack in particular was a defining moment for the band, and became a left-field anthem for a party that had just got a whole lot bigger.

Deadbeat Club, which preceded Love Shack on the album, was a fitting coda to all that bona fide smash hit single stuff. Heard accompanying its video, Deadbeat Club is an insightful and deceptively moving piece of personal history as much elegy as show of strength. In its underlying ennui concerning times past, the song is a melancholy paean to lost youth. It’s also a musical prayer to long-term friendships between small town oddballs bound and defined by a very special gang mentality through shared experience forever after. The song’s upbeat yearnings are shot through with the gut-wrenching ache of loss.

Listening to it cold, one could be forgiven for not spotting any of this. If you’re young and stupid, and without a care in the world because you’re partying hard with a deadbeat club of your own, all you see and hear is the fun, fun, fun of it all. Deadbeat Club may be fun at first, but beyond that, it’s a song in search of salvation.

Its opening spoken-word interaction features a faux-horrified Wilson yelping ‘Huh? Get a job?’ as if just routed for her lazy ways by exasperated parents. ‘What for?’ deadpans a laconic Pierson as only bad influences can. “I’m trying to think,” Strickland chips in before he’s overtaken by the wake-up call drum-thwack ushering in the Byrdsian guitar jangle that drives the song.

The first two lines, sung by Wilson solo, set the tone. ‘I was good, I could talk a mile a minute’ she reflects. ‘On that Caffeine buzz, we were on,’ she continues, before Pierson interrupts her reverie to join in with a joint ‘We were really humming.’

The unison of their vocals gives the song a swagger, like Wilson and Pierson are revelling in their bad gal act they’ve perfected before continuing.

‘We would talk every day for hours’ they sing, ‘We belong to the deadbeat club’, their us- against-the-world spirit of terminal adolescent defiance basking in their own myth-making.

‘Any way we can / We’re gonna’ find something,’ they sing, not quite sure what the night will bring, but going all out for it anyway.

Then, in a mind-flipping instant, ‘We’ll dance in the garden in torn sheets in the rain’. They sing it twice like they just had the best idea ever, before going into a chorus supported by Schneider now the gang’s all here.

The second verse finds Wilson and Pierson singing about going down to Allen’s, a real-life Athens bar where they can drink a 25 cent beer while listening to garage-pop classic 96 Tears on the jukebox.

‘We’re wild girls,’ they declaim in case you hadn’t spotted it, ‘Walkin’ down the street.’ They follow up with an inclusive ‘Wild girls and boys / Going out for a big time.’

By the third verse things are getting out of hand. ‘Let’s go crash that party down in Normaltown tonight’ Wilson and Pierson dare, referring to another real life Athens landmark. ‘And then go skinny dipping / In the moonlight.’ If Normaltown sounds like the sort of strip-cartoon suburban dead-end the B-52s might just have invented, there’s a romantic bravura to the image of what they get up to there after dark.

Intoxicated now and getting cockier by the second, Kate and Cindy stress the point about being wild girls and boys before going into the chorus once more. This is followed by a parting refrain of of ‘Oh, no, here they come, the members of the Deadbeat Club’ before wandering off into the night to cause mayhem elsewhere. As a withering kiss-off to the local squares who might be complaining about the noise, the company they keep or any darn thing at all, it’s deadly.

Deadbeat Club was initiated by Keith Strickland, who up until Ricky Wilson’s death had been the band’s drummer. It was Strickland who proposed a regrouping of the B-52s following a two-year silence. Having co-written much of the band’s music with Ricky, Strickland moved onto guitar, and took the music for what would become Deadbeat Club to the rest of the band.

They in turn picked up on some of the memories the music conjured up, of their carefree early days partying hard when Ricky was still alive. Hanging out in cafes and bars all dressed up in drag glam gear in a conservative college town in America’s deep south, the quintet really was referred to as deadbeats. Incidents from that era became a lyrical narrative that Strickland has described as probably one of the most autobiographical B-52s songs ever written.

Given that every neighbourhood in every town ever had an equivalent deadbeat club, made up of all the teenage misfits, oddballs and freaks who clung together for comfort, turning their outsider status into an asset, the song transcended its roots to sound defiantly anthemic.

In this sense, for all the fun, games and cartoon-styled capers that went with them, we should never forget just how subversive the B-52s were, and how deeply political such a construction remains. Here was a mixed gender quintet made up of three gay men, one bi- sexual woman – none of whom were out when they formed – and the guitarist’s kid sister.

As Wilson has put it, they were ‘two peaches and a bunch of nuts’, who married Peter Gunn detective theme surf-garage guitars and science-fiction schlocky horror keyboards to free- associative surrealist poetry. The wordless squeaks and squawks of Rock Lobster even looked to Yoko Ono for inspiration. This was picked up by John Lennon, who recounted in an interview with the BBC not long before he was murdered how he heard Rock Lobster in a club in Bermuda and declared to himself how he should ‘Get out the axe and call the wife’. John and Yoko’s album, Double Fantasy, was the result.

As for the the B-52s, Rock Lobster set the tone for a series of call-and-response narrative vignettes mashed up from a pop cultural pick-and-mix that were more routines than songs per se. Kate and Cindy’s harmonies are knowingly reminiscent of ’60s girl groups, but with a left-field top-spin that drew from Ono, only with a more consciously and at times comically libidinous intent. There’s a raw catch in both Pierson and Wilson’s voices possessed with an oomph that goes beyond technique. When, caught up in the unfettered good-time euphoria of Love Shack, the song pauses a second to allow Wilson to give vent with a filthy-sounding ‘Tiiiin roof / Rusted…,’ you somehow know exactly what she means. As for Dirty Back Road, well….

In many songs, Kate and Cindy are egged on by Fred, whose cosmic interjections and asides resemble those of an evangelical MC, a ringmaster of mirth leading from the front with attitude aplenty. In the video for Deadbeat Club, Schneider can be seen proffering an album cover to the room as a wild card suggestion to put on the record deck next. Compared to such big personalities, Strickland may appear quieter and more in the background, but his role as the band’s de facto musical director is crucial.

When Deadbeat Club and its parent album were released, the B-52s had been around for more than a decade. Schneider and Strickland were already in their late thirties, with Pearson in her early forties. The youngest of the band, Wilson was 32, the same age as her brother when he died.

Without referring to it directly in any way, it was the video for Deadbeat Club that brought this home. Made at a time when MTV was king and video budgets were big, Deadbeat Club was directed by Jeff Preiss. The year before, Preiss had been cinematographer on Let’s Get Lost, photographer Bruce Weber’s black and white documentary study of jazz trumpeter and singer Chet Baker. Footage moved languidly between archive images of Baker the beautiful icon of 1950s’ cool, to the old man whose looks and musical prowess had been ravaged by heroin addiction.

The colour-clashing riot of the video for Love Shack and the green screen travelogue of Roam were both directed by Adam Bernstein, who would go on to win an Emmy award for his work on TV series Fargo. After such japes, bringing Preiss in marked a radical change in tone. Deadbeat Club was duly filmed in a similar verite style to Let’s Get Lost in gauzy black and white.

The first thing you see is a close-up of Cindy’s face, her big eyes looking vacant and ever so slightly wasted as she lays back in that three-quarter length leopard-skin coat she wears throughout many of the video’s moments. She mouths her ‘Huh? Get a job?’ line directly to camera, which cuts to Pierson and Strickland as they complete the dialogue before the song kicks in proper. As the guitar comes in, the camera cuts to a highway scene of two open-top cars. Kate and Fred are in one, Cindy and Keith in the other, with the women at the driving wheel of each.

Over the next four minutes or so, the camera flits in blink-of-an-eye succession between two or three party scenarios, with the band in different outfits in each. There’s Fred striding his way towards the sort of wood-lined club-house you’d like to imagine the B-52s lived in together the way the Monkees did. Inside, the party’s in full swing. There’s Keith with a candelabra on his head, and others sharing intimacies on the sofa. And look, there’s Fred and Kate on the couch, before someone giddily falls off the arm-rest while trying on shoes.

Outside, there’s Keith on a bike in a hip suit. Cindy wears a feather boa, and beams at the camera. Both she and Kate wear their hair high. Except when Cindy dances close to the bonfire or sways by the trees like some hippy chick left over from Haight-Ashbury while Fred wears a jacket so sparkly he might have liberated it from Liberace’s closet.

One minute it’s early evening, the next it’s almost dawn, with all five band members on the highway with wind in their hair like real live movie stars, except better dressed. Everything seems to come in retro patterned fabrics, from Fred’s cardigan and the pet dalmatian who pads about the room, to Kate’s cocktail frock and of course Cindy’s coat.

When Kate sings her ‘Wild girls and boys’ line in the song’s final verse, her hands-on-hips sass is counterpointed by Cindy’s comic eye roll to the side as she lays in repose. In the song’s fade-out, she’s on her feet, posing in mock admonishment to whoever’s behind the camera, trying to catch her attention.

As the lens moves between all this, it does so, not with rapid-fire jump-cut brutality, but with the leisured eye of a bemused onlooker attempting to capture every moment for posterity. As it’s remembered in the morning-after jumble of flashbacks, time gets mixed up and incidents blur into each other. For the entire video, no-one seems to stand still for a second. All they do is dance and spin in a whirl of perfect motion, like nothing else matters but that moment.

While Kate, Cindy and Fred lip-synch throughout, it all appears au naturelle, as though the good times were for real and were never going to stop. This may go some way to explaining the glazed look in Wilson and Schneider’s eyes especially, as well as the series of seemingly unguarded moments the camera focuses on outside the song itself.

In an email exchange, Preiss recalled making the video almost three decades ago, long before he directed his 2014 feature film, Low Down, about the life of jazz pianist Joe Albany. Preiss remembered filming Deadbeat Club in Athens, casting the band’s friends and using their homes as locations. Preiss also remembered how he and his crew “basically tried to not get in the way of the joy produced by the music. I mean, the music and the sound produced by Kate and Cindy’s voices is so powerful in that way (plus Fred’s voice as a kind of ironically commenting one-man Greek chorus).

“The idea of the video was just as simple as that. The song looks back on memories of friendship and a joyful feeling of freedom that’s virtually subversive in its existing for its own sake. So we looked for it.

“At the same time we tried to exploit our love of movies – movies with wild party scenes in particular – and tried to make it loop back onto itself: people who love La Dolce Vita celebrating their mirroring of La Dolce Vita in order to produce their own version of La Dolce Vita. it was actually an incredible time in the making!”

Beyond the excess, as with every party, it’s the private times that count, the solitary come- downs and pauses for thought when every pleasure seeker has to call time out and take a step back into their own world awhile. It might only last a second, but such fleeting moments matter. It’s the way Kate and Fred dance with a fervour that borders on staggering out of control, but which somehow keeps its balance.

Kate bumps, grinds and shimmies like she’s stepped out of I Dream of Jeanie. Fred throws slo-mo shapes, his Liberace jacket and whitened face giving him the other-worldly air of a Kenneth Anger character worshipping the sun. Then there’s Keith, where he was all smiles earlier, now sombrely nodding to the music, internalising the experience. There he is again, alone and noticed only by the camera, contemplating his own thoughts, lost in a zen funk.

And then there’s Cindy, in that coat, dancing perilously close to the bonfire, spinning as she barely mouths the chorus. And there she is again, sat on her own, hair towering above her. Her eyes only flick to the camera when seemingly prompted, so she stares as if posing like Penelope Tree or some other Warhol superstar, possessed by an ineffable sadness that’s over in an instant.

Such is the unbearable lightness of being the B-52s, the self-styled world’s greatest party band party band who life got in the way of, and who, on Cosmic Thing and in the Deadbeat Club video in particular, appear to be walking the shadow-line between innocence and experience. This is done with a sense of in-the-moment intoxication which, the way the footage is cut, appears to have mood-swings as it tries on different personalities from the B-52s dressing-up box for size.

Preiss would go on to do something similar for fellow Athenians REM on the video for Near Wild Heaven, the third single from the band’s 1991 Out of Time album, which, like Cosmic Thing for the B-52s, moved REM into the mainstream. REM vocalist Michael Stipe had made an appearance on the sofa in the Deadbeat Club video, and Kate Pierson duetted with Stipe on Shiny Happy People, Out of Time’s cheesiest and most consciously pop track that was arguably the album’s equivalent of Love Shack. Such criss-crossing connections amongst Athens’ disparate musical community go further. Stipe’s sister Lynda sang and played bass with Oh-Ok, whose song, Brother, Cindy Wilson would go on to cover on Change.

When the video for Deadbeat Club was made, the B-52s were twelve years and five albums old. In that time they’d gone from cult club status to global stardom, infiltrating the mainstream with pop art subversions that came gift-wrapped in fancy dress. When Ricky Wilson died, the original deadbeat club gang lost a limb that could never be replaced. Like all gangs, that loss made them stronger, with Cosmic Thing the result.

In the three decades since, there have been two other B-52s albums. Good Stuff came out in 1992, with the band reduced to a core trio due to Wilson taking a sabbatical to raise her family with husband Keith Bennett. Wilson met Bennett the night of the first impromptu B-52s performance back in 1977, and he went on to become Ricky Wilson’s guitar tech, with the couple marrying a few months before Ricky’s passing.

It would be another sixteen years before the follow-up to Good Stuff, Funplex, would appear in 2008. Inbetween, the three-piece B-52s became the BC-52s for the 1994 Flintstones movie. Wilson returned to the fold to record two new songs for the 1998 retrospective, Time Capsule: Songs for a Future Generation. One of them, Debbie, was a joyous homage to Blondie’s Debbie Harry. The video for the song featured Wilson sporting what looked like that three-quarter length leopard-skin coat again.

More recently, both Pierson and Schneider have released solo albums. Several years prior to her own current solo releases, under the name The Cindy Wilson Band, Wilson recorded Ricky, her most explicit statement on the loss of her brother.

In 2012, Strickland retired from touring with what is now a group of sixty-somethings (Pierson has just turned 70). Age isn’t stopping the rest of the B-52s spending much of 2018 on a 46-date North American tour in a spirit that echoes the title and spirit of the very last track on Funplex, Keep This Party Going.

Almost thirty years on from it being filmed, the Deadbeat Club video looks like a home movie, a time capsule of a band mythologising themselves in close-up, grabbing every moment of pleasure they can before the fun stops and la dolce vita grows tired. Individually and together, Wilson, Strickland, Pearson and Schneider party hard, laugh out loud, dance like there’s no tomorrow and, if you look closely amongst the merry-making, take a moment out to reflect on who they are and how they got here. At the end of the video, with just the four band-members in repose and all the party-goers departed, it’s as if they’ve finally found time to be themselves again.

Up until Cosmic Thing and Deadbeat Club, the B-52s entire raison d’etre was a day-glo teen- dream response to small town life and the desire, one way or another, to get out of it. This was writ large whether putting on some vertiginous bouffants and heading to the neon side of town in Wig, kissing tummies and pineapples in Strobe Light, or else entering the twilight zone of Planet Claire. There was the turbo-charged brattiness of Give Me Back My Man and Dance This Mess Around and the resigned disappointment of Ain’t it A Shame. There was also the bible belt social satire of Devil in My Car, but even that suggested an embracing of everything that was weird, however oppressive it might be.

Cosmic Thing was different. Slicker, smarter and sassier than previous records, Cosmic Thing was a homecoming, a prodigal’s return of local boys and gals done so good they could record a hymn to globe-trotting such as Roam. The album was also an unconscious attempt at closure, as the four surviving B-52s, older and sometimes wiser, re-engaged with their roots. Where any sense of nostalgia in their music had been imagined and exaggerated to the nth degree, Cosmic Thing was pulsed by an authenticity that gave it both poignancy and strength.

Watching footage of Kate and Cindy performing Deadbeat Club on the B-52s 40th anniversary tour, with Cindy resplendent in blue wig and Nefertiti-like robes, saw them put as much heart and soul into the song as they did on the Cosmic Thing tour back in 1990. This was the case even if neither Keith nor Fred were on stage with them and the long-term session band this time out.

Whether the B-52s make another record or not, the legacy of Athens GA’s original deadbeat club is secure. Take a look at the video for Wilson’s single release of Brother. Filmed outdoors in shiny happy colour and directed by Lance Bangs, the clip features Wilson and her young band in a similar looking location to where the Deadbeat Club footage was shot. Now, as then, there is much fun with fancy dress, bicycle rides and general goofing around.

If Deadbeat Club was a purging in disguise, like Brother, it looks and sounds like a real life song for a future generation. Wilson and the B-52s are still keeping the party going, wild girls and boys taking it as out of bounds as they can. Maybe if we all head over to the neon side of town we’ll find them there, all their yesterdays wrapped up in a three-quarter length leopard-skin coat, dancing for eternity.

*

If you enjoyed this article, why not make a donation to Product? We’re an independent publisher with charitable status (SCO 29793). The magazine is edited, designed and produced by volunteers, with all contributions of time, skill and content given for free. We showcase work by new writers, artists and photographers at an early stage in their careers, many for the first time. A small donation can make a big difference towards the running costs of the magazine. Please donate here: