Beyond Rock and Roll

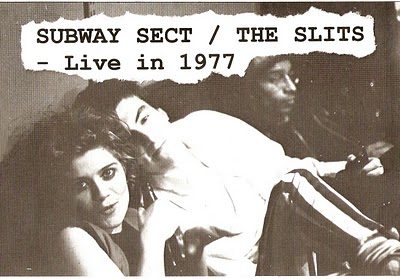

October 15, 2016. Onstage at the Wee Red Bar, ostensibly Edinburgh College of Art’s student union but so much more besides, the living legend that is Vic Godard is baring his soul. The louche front man of Subway Sect, whose support slot to The Clash on the Edinburgh Playhouse date of the iconic headliners’ May 1977 White Riot tour effectively spawned what became known as the Sound of Young Scotland, has just sung backing vocals to his own song, Ambition, as performed by The Sexual Objects. The Sexual Objects, of course, are fronted by Davy Henderson, one of those in attendance at the Edinburgh Playhouse show. His incendiary band, Fire Engines, were key figures in Scotland’s post-punk renaissance, before morphing into glossy New Pop pioneers Win. Henderson got back to basics with The Nectarine No 9, then embraced all that’s sublime about rock music with the Sexual Objects. And now here they are, playing Ambition while the song’s visionary writer takes a step back as Henderson sings lead vocal on a version that sounds more jagged than the Subway Sect original, but just as oppositionist and anthemic.

The Sexual Objects have been regular gigging partners with Vic Godard for some years now on what has become an annual Scottish sojourn. Henderson and co have even mutated into the magnificently monickered Sectual Objects since the umbilical link between them was connected at a 2011 Edinburgh Book Festival event in honour of the late poet Paul Reekie. Another of those in attendance at Edinburgh Playhouse, Reekie also fronted the band Thursdays, and ran the Edinburgh branch of the Subway Sect Fan Club.

Five years on from the Book Festival, and here was Vic and the SOBS once more giving an even more poignant performance that was never meant to happen. Or rather, it was meant to happen, like it’s been happening for years now on a more or less annual basis, with Vic and various line-ups of the Subway Sect appearing a couple of times at Citrus before moving across town to the Voodoo Rooms. Now here he was booked to play the Wee Red Bar on what had increasingly started looking like a never ending tour.

Vic’s ongoing renaissance had seen his life partner and wife George, aka the Gnu, become an integral part of operations. She always was, whether it was running the merch stall, developing the ever-expanding website that documented Vic’s back pages, or putting out limited edition tour CDs on the Gnu Inc label. I have two treasured Subway Sect mugs in my kitchen that I bought off George.

The Wee Red Bar show was a Gnu Inc production. That in itself made it sound special, like an old school package tour, and on the door there were going to be free CDs recorded at a Vic & the Sexual Objects show in Glasgow in 2013, and chocolates with specially printed up wrappers for the occasion.

A week or so beforehand, however, the gigs on the Gnu Inc tour started being cancelled. Newcastle was the first one I spotted, where Vic and the Subway Sect were supposed to be playing alongside the Band of Holy Joy. And when Edinburgh went, you knew it was serious. Gradually, it came out that George had been diagnosed with a vicious form of cancer, and had passed just a few nights before the Wee Red Bar show had been due to take place.

The Sexual Objects would still play, but would now be supported by Shock and Awe, whose singer Murray records Vic’s shows pretty much every time he comes to town. Some of Murray’s recordings have been released as official bootlegs. All of which is kind of great, even though everyone is really thinking about Vic.

Walking along Lady Lawson Street on the way up to ECA, I see a figure coming towards me clutching a mobile phone to his ear. It’s Vic. He’s in deep conversation with someone or other, and given everything that had happened, it’s a shock to see him.

When I get to the Wee Red, Murray’s on the door. He gives me the free tour CD of Vic and the SOBs playing Make Me Sad, as well as two chocolates with a customised Gnu Inc Presents wrapper to mark Vic’s appearance at the Wee Red. I tell Murray about seeing Vic on the street. Murray looks anxious, and says Vic had decided to come up, but wasn’t playing. He’d got someone to give him a lift. Well, what else was he supposed to do?

Inside, a slightly muted atmosphere pervades. Everyone’s out, and for a student union to be filled with so many ageing post-punks must be odd for the Wee Red’s young bar staff. People are hugging each other as they arrive, and that’s pretty normal these days, because it’s a room full of friends, some of who you recognised, others not so much, and they were all good people. But tonight feels different. At one point I lean in to Tam Dean Burn and whisper that it feels like a wake.

For much of the Shock and Awe and Sexual Objects sets, Vic sits by himself up at the side of the bar at the back of the room. Yet there he is at the end of the SOBs set, a little to the side of Davy, as if from nowhere. He stands out because, unlike everyone else onstage, he isn’t wearing shades like he’s playing Warhol’s Factory circa ’66. And seeing Vic sing backing vocals on Ambition, a song he must’ve sung a million times before, is weird, but we’re with him all the way.

Somehow at the end of the song which is also supposed to be the end of the set, Vic stays on his feet in the stage area, and he clearly wants to talk. He talks about George, not about her death, but about her life and the life they shared together, through punk and heroin addiction and him being a postman. But Vic isn’t being maudlin in any way. He’s joking, and is being quite the raconteur, and he tells the band, who’ve been standing behind him for a few minutes now, hiding behind their shades, to play something.

Someone brings Vic a stool which he sits on while the SOBS jam out low-key Velveteen guitar patterns that recall Sunday Morning or Pale Blue Eyes, but which are very much of the SOBs’ own making. And Vic’s still talking, telling stories in this long rambling monologue, which is the sort of thing I recognise from every time I’ve interviewed him on the phone, except this is different.

Vic’s talking about a book he’s going to write that will be full of all these stories, and it’s never indulgent, and the audience, who are all friends of one form or another, don’t say a word, because again, we’re with him. They listen, they laugh, but the laughter’s never forced. It’s genuine and it’s quiet, because it’s Vic and he’s lost the love of his life and he’s sharing all these funny stories with us because this is clearly something he needs to do. And what started out as a strange and slightly muted night has just become something very special and very beautiful.

Vic Godard has been an on-off part of my musical life for more than three decades. I was just that bit too young to catch punk’s first flurry in any meaningful sense, although my pre-pubescent self loved the idea of it all. I bought singles by the Stranglers and the Sex Pistols before moving onto Buzzcocks, Magazine and Joy Division. Echo and the Bunnymen and Teardrop Explodes came next, before Orange Juice, Josef K and Fire Engines opened things up to other, increasingly endless possibilities. Somewhere in the thick of this came Subway Sect.

The first time the name fully registered was when I saw an ad for a Buzzcocks’ gig in the Liverpool Echo. I’d already cottoned on to Buzzcocks’ cracked love songs like What Do I Get? and I Don’t Mind, and this band called Subway Sect who were supporting them sounded right up my street. I wouldn’t hear Nobody’s Scared and Ambition for a good while yet, let alone read about how Malcolm McLaren told Vic and the others they should form a group, and how after they formed Subway Sect and played the 100 Club Punk Festival a couple of weeks later, Bernie Rhodes took them under his wing and then sacked all of the group except Vic.

Whatever they sounded like, it was a great name, Subway Sect. Rather than just being a bunch of losers talking up some myth-making counter-cultural credentials, the name implied some samizdat alliance that actually was underground. They were still a gang, but the name made it sound cleverer and more organised, like they had something to believe in.

The fact that their singer’s name was Vic Godard made them sound even odder. I mean, what punk band in their right mind had a singer called Vic? It sounded like your pub crooner uncle who did Sunday night turns doing bad Sinatra impressions in chicken-in-a-basket social clubs had infiltrated the scene. And as for Godard… When everyone else was being Rotten and Vicious, with their bad boy roots more akin to Fury and Wilde rather than Glitter and Stardust, who the hell was Godard?

One music paper article talked about Vic washing dishes in greasy spoon cafes and reading Sporting Life. In the interview itself Godard talked about Radio 2, French films and Northern Soul. All of which sounded as un-punk as it could get. It could have been affectation calculated to keep the music papers happy, or else it could have simply been the day to day concerns of a post-punk existentialist in a still cheap and ungentrified London. And French films, you say? Oh, that Godard.

Edwyn Collins of Orange Juice had started talking Vic up, and Orange Juice covered one of Vic’s songs, Holiday Hymn, on a John Peel session. It sounded like vintage song-writing that predated punk and wouldn’t have sounded out of place with a big band arrangement wrapped around it. But how on earth did Orange Juice get hold of it when Vic hadn’t even released it himself yet?

I bought the 7” single of Stop That Girl, a song which featured an accordion as lead instrument and was apparently about a bloke being warned to keep a close eye on his girlfriend in case some lesbian who was hanging around made a move on her. It was a song with a narrative, like a little Play For Today had been condensed into this post-punk chanson that had roots on both the Left Bank and Tin Pan Alley.

I picked up a copy of the What’s the Matter Boy? album, the front cover of which had a cut out picture of Vic standing with his hands in his pockets wearing a V-neck and smoking a fag in front of a tinted red-brick back-drop. The back cover had a cartoon image of a duffel-coated artist type smoking a pipe, a flappy portfolio under his arm. There’s graffiti about Sartre on the wall of the Rue des Saints Peres, where a sultry looking young woman keeps her hands in her split skirt pockets as she draws on a cigarette. And that was before you even played the record.

What’s The Matter Boy? sounded like a set of short stories you could sing along to. With titles like Birth & Death, Empty Shell and Exit, No Return, they were more articulate and profound than both moon-in-june banality and the sloganising rhetoric which in parts had replaced it. Watching the Devil sounded like it should be performed in a gentleman’s club, Split Up the Money and Stool Pigeon were caper movies in waiting. What Vertical Integration might be was anybody’s guess, though it was a jaunty enough song anyway. The closing Make Me Sad, meanwhile, was just, well, heartbreaking. As with Stop that Girl, What’s the Matter, Boy? was timeless, like it was something which had come before rock and roll, but also something beyond it.

By the time I’d caught up with all this, Vic was already morphing into full-on crooner mode with Club Left, the London cabaret night founded by Bernie Rhodes, where Vic and his all new Subway Sect were both house band and top of the bill. Rather than wearing v-necks and baggy trousers, now Vic sported a bow-tie and penguin suit and smoked through a cigarette holder. Where previously he’d appeared on an NME cassette with a rough version of Parallel Lines, now he was on another one with a cover of Cole Porter’s Just in Time. Swing was the thing, and all that talk about Radio 2 had come home to roost.

Someone, presumably Rhodes, had the bright idea of sending Vic’s jumping, jiving version of Subway Sect out on a tour that saw them sandwiched between headliners Bauhaus and opening act the Birthday Party, fronted by a young and demonic Nick Cave. I saw them in June 1981 at Liverpool’s Royal Court Theatre. As you might expect, a quintet of men in lounge suits playing a set of what sounded like old-time standards to a room full of goths didn’t exactly go down a storm.

The things I remember from that night were Nick Cave rolling round in the orchestra pit, crazed, half-naked and possessed, shrieking like a wounded banshee. And I remember an unopened can of beer being hurled at the stage and smacking Vic full-on in the face. We didn’t stay for Bauhaus. I’d seen them the year before supporting Magazine and I knew how awful they were. Besides which, in the wonderland that was Granada TV in those days, a nascent New Order were on telly for a full half-hour at half past ten on an arts programme called Celebration, and in the days before anyone had videos or iPlayer, these things mattered.

In the autumn, Club Left went on tour, with Vic and the Subway Sect headlining a bill that also featured rockabilly singer Johnny Britton and a nouveau jazz chanteuse called Lady Blue. The Liverpool date was part of a night called Le Son Divin, and was set to take place on the Royal Iris.

The Royal Iris was a Mersey ferry that did pleasure cruises around the river, picking people up and dropping them off at Liverpool and Birkenhead. You could hire the boat out for parties, and in the sixties, I later found out, the Beatles had played there.

With the night MC’d by Rhodes, the Royal Iris was perfect for Club Left. In truth the faded grandeur and sticky-carpets of any of the hundreds of nightclubs that lit up town as if they were spotlighting the next day’s walk of shame in advance would have worked just as well.

To an audience of young women in retro cocktail frocks and red lipstick, and men with slicked-back hair and baggy suits, Johnny Britton battered his guitar into submission, and Lady Blue cooed sweetly. Then there was me, with my Army and Navy stores overcoat and surplus Boy Scout trousers, trying my best, but not having much of a clue either. When Vic came on, he and the Sect got through their set unscathed. Mercifully, there wasn’t a goth in sight, and they played a blinder. I may have only tapped a toe, but inside I was jiving.

I don’t really know what happened to Vic after that. Within eighteen months, the swing-time version of Subway Sect were on Top of the Pops, backing up American singer Dig Wayne as JoBoxers. JoBoxers dressed like characters from a 1940s gangster flick and had a few hits before disappearing. I heard the drummer got off with a girl I liked who wore a Bauhaus t-shirt because she liked the picture on it rather than the band, but Vic was nowhere to be seen. The T.R.O.U.B.LE. album came out, but the moment seemed to have passed. I’d moved on, and so had Vic, who I heard became a postman. Or a junky. Something like that.

It was probably the 1990s before I stumbled across Vic again. I picked up his The End of the Surrey People album on a briefly revived Postcard Records, with Edwyn Collins producing and former Sex Pistol Paul Cook on drums. There were compilations, and a couple of low-key gigs in Glasgow. The lounge suits and bow tie had gone, but Vic still played Ambition, as well as some new songs with various line-ups of a newly constituted Subway Sect.

Vic started to appear more in Scotland, and formed some kind of affinity with Creeping Bent, who at that time had started putting out records by the Nectarine No 9, the latest vehicle for Davy Henderson, who’d been burned in the 1980s pop wars with his band, Win. The first album by the Nectarines had been released on Postcard, who had also put out The End of the Surrey People. I wrote about Vic for the first time, and on the phone it was hard to stop him from going off on tangents about Bernie Rhodes and bands like the Bitter Springs and Edwyn and all of that.

At some point in the late ’90s I ended up putting on an over-crowded Creeping Bent gig at the old Cafe Royal, which is now the Voodoo Rooms. The Nectarine No 9 were headliners, and sound-checked forever, so everything ran over way too late. The lights were on and the bouncers were getting antsy by the time the Nectarines kicked into their last song, but they were going to finish it whatever. Especially as Paul Reekie had jumped onstage in a kimono to sing a version of Johnny Thunders, a song that Vic had written in 1990 after he’d started making music again when George bought him a guitar.

More albums followed; Long-Term Side-Effect, Sansend, and We Come As Aliens. Then there was Blackpool, the end-of-the-pier musical Vic wrote songs for with Irvine Welsh, and which was performed by drama students when Queen Margaret College was still on Leith Walk. Eventually an EP of songs from the show appeared. Vic kept on coming back to Edinburgh.

Vic was still doing his post round, and I interviewed him again while he sat in his back garden in Kew, where he’d listen to the test match on the radio after he’d finished his deliveries. That might have been before the show at Citrus in 2007, when he forgot the words to Ambition because he started thinking about George making his sandwiches for work. He told me about the cover of Make Me Sad he did in Sweden with a group of four postmen. Then there was the day later on when we were scheduled to do a phone interview together with Paul Cook, who was back on tour with Vic for a bit.

When I called, the phone was picked up by a sheepish Vic, who’d arrived late for Subway Sect rehearsals, provoking the wrath of Cook, a hard taskmaster who’d become Vic’s informal musical director, and for whom good time-keeping was seriously important. So important, in fact, that Cook’s bad temper meant he was no longer up for talking to me. I wrote the article anyway, but the paper refused to publish it without a Sex Pistol involved.

On the 1978 Now and 1979 Now albums, Vic revisited the really old material, the punk and the Northern Soul which he’d been doing before What’s the Matter Boy? and Club Left. There had already been the 20 Odd Years compilation, and now there was the 30 Odd Years double CD trawl that rifled even further through Vic’s back pages.

Two years ago, Vic got all dressed up to revisit Club Left for a date at Glasgow Jazz Festival, where the swinging version of Subway Sect reformed for a night. For some reason or other I couldn’t go, but even though I wasn’t there, inside I was still jiving. This year, Summerhall in Edinburgh had a screening of Derailed Sense, a quasi-gonzo DIY documentary on Vic that saw him uncharacteristically reticent in front of the camera. And suddenly here we are in the Wee Red Bar listening to Vic Godard bare his soul and talk to us the way he does because he has to.

The plethora of activity over the last few years seems to be Vic catching up on himself, making up for lost time, and everyone in the Wee Red Bar that special night has George to thank for that.

Now here we are a year on, and Vic’s back at the Wee Red Bar this weekend with the Sexual Objects and, as an extra bonus, the Secret Goldfish, who’ve also done covers of Vic’s songs. The same line-up play Glasgow the next night, and both shows are presented by Sounds in the Suburbs, the lovely little one-man operation who’ve put Vic on in Scotland many times before.

Word on the street is that Vic is in fine fettle. He’s doing loads of gigs, and the night before the Wee Red show he’s doing a session on Marc Riley’s BBC 6Music show. Vic’s released a limited edition 7” on Gnu Inc records. It’s called Can’t Take the Sunshine Away, opens with the sound of waves crashing against the beach, and, like the B-side, Inertia, harks back to the old school jazz of Songs for Sale and T.R.O.U.B.L.E. era Sect. This is a trailer for a forthcoming album called Mum’s Revenge, which is still a work in progress, though Vic says it should be full of surprises.

Word is as well that Vic will be manning the door of the gigs himself, and that there might even be a bit of spoken word. Whatever happens, it will no doubt be wonderful, and Vic will carry on doing what he does. And when the book comes out, because it has to, it will be full of stories, about Subway Sect and Bernie Rhodes and all the 1978s and 1979s now and then. But most of all it will be about Vic and George and the Gnu, and everything that happened before rock and roll, and everything beyond it too.

Vic Godard & Subway Sect, The Sexual Objects, The Secret Goldfish, Wee Red Bar, Edinburgh College of Art, Edinburgh, Friday October 20th; Admiral Bar, Glasgow, Saturday October 21st.

An earlier version of this article first appeared in The Leither magazine.