Aces High

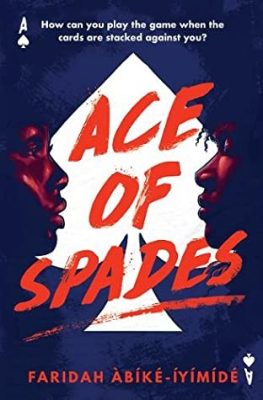

Few recent books have captured the popular imagination more than Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé’s brilliant debut Ace of Spades. Pitched as a YA thriller along the lines of “Gossip Girl meets Get Out, but gayer” it centres on the only two black students at a prestigious high school, Niveus Academy. Devon, a promising musician, and ambitious head girl Chiamaka are thrown together when their personal secrets are broadcast by a sinister anonymous texter, Aces. The book combines formidable story telling with noirish episodes, and a contemporary take on staple teen drama elements of love, rejection and friendship. Àbíké-Íyímídé excels at articulating her young characters’ feelings of isolation and despair and pulls no punches in her moving depiction of racism and homophobia. Born and raised in London, Nigerian Àbíké-Íyímídé wrote Ace of Spades while a student at Aberdeen University.

What inspired you to start writing in the first place? My Mum inspired me! She would always read to me when I was younger. Sometimes she would just make up stories, sometimes it was folklore. And so I always wanted to be able to tell the stories the way she did, to take someone on that transformative journey. I just really loved being read to, because I’m dyslexic. I really struggle with reading myself and so I was really obsessed with one day possessing the ability to tell a story and help someone to go on that journey of being lost in a story.

When was your dyslexia discovered? I discovered it when I was in university: there were a lot of factors that went into why it wasn’t picked up on when I was younger, because a lot of early reports from my childhood spoke about this weird tendency I would have to say or spell words wrong. Well into my GCSEs, I had messy handwriting or just generally grammar and spelling being really off, and they didn’t match my level because I was in the top sets. No one ever thought to test me for that because they usually didn’t test people in the top sets and they also didn’t tend to test kids of colour. So I didn’t fit the model of what they assumed a dyslexic child looks like. And so it wasn’t until I got to university where Student Support spoke to me and suggested a test. It was so late in my life that I wish I had that earlier.

Do you feel your success has allowed you to help dyslexic children? I really hope so. Because I feel like I definitely think not knowing I was dyslexic made me I guess, maybe maybe not feel as I don’t know, I don’t want to say bad but…I have friends that were dyslexic growing up and often knowing that and the teachers knowing that they were treated a bit differently. People didn’t treat them as if they were capable enough. So I think, hopefully, me being so open about it will really help children with dyslexia.

Please tell us how you got from being an unknown, unpublished writer to Ace of Spades being published. I always wanted to be a writer. Around the summer when I was 17 I decided to look into what it means to be a writer and how people actually get from concepts to publishing a book, seeing it in Waterstones. I’d been following this author online. Her name is Alice Oseman and I saw at the time that she had got a publishing deal, when she was 17, and it came out when she was 19. And I was like: people my age can be published and published by big publishers. And so I started researching what it would mean to achieve that. And I came across resources online on what a query letter is and how to find a good agent. Then I was just literally researching constantly, watching videos, listening to podcasts on publishing. And then I began to understand what the trajectory looks like. I wrote three books before I got my agent and book deal. And that’s kind of how it is for people – you do a lot of research and then just keep on trying until it lands in the right desk at the right time.

Who have been your favourite writers or key influences on your work? People like Patrick Ness – I was a big fan of his books growing up and even now. David Levithan. Jason Reynolds – I’m obsessed with his work. I really love Andrew Thomas. Malorie Blackman, I really loved her growing up. I think also people like Jacqueline Wilson. I really loved seeing a female author on the shelves being so celebrated as well. And Holly Bourne. Yeah, I think definitely those type of authors are writing young adult fiction and writing realistically about teens going about their lives and experiencing things I could relate to. I really wanted to do the same thing they were doing in a way that felt compelling but also so entertaining. I really, really love those authors!

Was there one book that made you think – yes, I have to write? It was a few of them all at once. People like Tomi Adoyemi who wrote Children of Blood and Bone. Prior to her I had never heard of a Nigerian author before. So I was like: Oh, that’s so wild. An author like me can be published. And also Alice Oseman as I said – realising you can be published at any age. There’s no restriction as long as you’ve done the work and you’ve written the best book you can. You can do whatever you like. All those writers made me feel like I could see some part of myself in them, feel like I could do it if I tried.

What would your advice be to new young writers as a writer whose work addresses race, queerness and class? Do you think that the traditional routes to publication allow for diversity, or do you think certain groups are left disadvantaged?So I think, first part of the question on advice to younger writers is – don’t let external forces make you feel like you’re not good enough to be a writer. I think a lot of the time, people might look down on younger writers, or even discourage them. Anyone can be a writer even at 70 or 18 and they can below 18! I think that you should definitely make sure that your parents are aware, so that you can make sure that you have your parent consent but also make sure you’re being looked after and not exploited with a contract. Also, I would say that you don’t have to do well on the first try. You don’t have to even get a book deal before any age. People put pressure on themselves to accomplish so much before a certain age. You should be ambitious but also not beat yourself up if you don’t get where you want to be. And see the book as an opportunity. Like everything, your writing is an opportunity to just grow and improve. And as to the end of that question – in terms of writing, about race class, sexuality, gender – I definitely think there are barriers in publishing that make it harder for people that are marginalised in different ways to break in, especially because publishing is run by people that are not always from minority or minoritized groups. And so it might make it harder for them to understand your background. But I think definitely, there have been efforts in recent years to diversify for publishing. There are publishers like Jacaranda that are actively looking for people who are neuro-divergent, queer people of colour, to be writers. So things are a lot better than they were ten years ago in publishing, but at the same time, there’s a lot of room for change.

If you met someone who’d never heard of Ace of Spades, how would you describe it? I always like to use comparative titles to sum it up quite easily so that people can picture something in their heads. So with Ace of Spades, I always say it’s like a mix of Get Out with Gossip Girl. Or even like more recent examples of like media, I would say it’s kind of like Squid Game meets Pretty Little Liars. Just kind of dark and twisted. Horror meets teenage drama that you see in mystery traditions.

The book is written from the perspective of Chiamaka and Devon. Which perspective did you enjoy writing more? I really enjoyed them equally for different reasons. There’s so many rounds of edits when you’re writing, sometimes I prefer being on one person’s point of view more than the other but I always feel an equal love for both of them. They’re so different that it’s always hard to compare the two. With Chiamaka, I really liked writing someone so mean or unlikable.

Yes, at the start she’s horrible. (Laughs) I found that really fun because in real life, it’s hard to be that mean and not get the consequences of it. It’s almost like fantastical because she’s quite privileged, she doesn’t really care how people react to her because she feels like she has kind of all the things she needs to take them down. It’s fun being in Devon’s head because he’s quite sarcastic. So both have personalities that I admire, but also, I’m so different from them. I would really love to tap into that. Even if it’s vicarious it is kind of fun.

The two of them have different experiences of being gay. How did you approach that? I think because there’s no monolithic experience of any identity. I really wanted to highlight what two experiences could look like. There’s not really much representation for black queer people in the media. I really wanted to show that it wasn’t one way and how other things can influence the way you experience one attribute of identity: for example, the one being poor definitely feeds into the way he experiences his sexuality, or even being a person with immigrant parents because you know, some people have to think about what the repercussions will be going back home to the country of their birth families. It’s just so many aspects of your personality and your identity influence the way you experience your marginalisation. It’s important to highlight the way people are not monoliths, and how being queer is something that different people approach differently. For Chiamaka, she’s privileged, many things in life have been quite easy for her. But because she’s a black woman, she’s having to think of so many things at once that like, sometimes other aspects of her personality and identity have been more overt to people – that’s what she’s had to constantly combat. I just think it’s so important to just show how intersectionality works and how that affects you, and the way you experience aspects of identity.

The difference between them is also played out in terms of class. Yeah, I set out to put that in the story because I grew up working class and because of where I grew up, and the demographic of the area I’m from, I assumed wrongly that all black people were going to be like me – working class. I went to university and I found out that class didn’t mean anything. Not all black people are going to be working class, some are middle class, some were upper class and came from boarding schools, and had never struggled financially in their lives. So I really wanted to show how intersections of class and race affect people in different ways. In Ace of Spades there are white characters who are working class and I want to show what that looks like, there are white characters who are rich. There are black characters who are working class, black characters that are rich. I wanted to show how race doesn’t go away when you add in the class factor.

I liked the relationship of the two characters with their parents. Chaimaka has two and Devon has one. I really wanted to also show just the experience of different types of families. Like Devon has a single mother and I have a single mother as well. And it doesn’t always look how you might expect it to look, but sometimes it does. I feel like sometimes a lot of shame that people feel towards not having the family that’s normal to us from childhood. And I think it’s so important to demonstrate that in children’s books that you know, these families existed, it’s valid to grow up in this type of kind of home dynamic and structure but also that because it’s often the stereotype that you know, all black people have one type of family kind of structure. There are families that have two-parent homes, and there are some that don’t and you know, both can feel very lonely sometimes because as you can see Chiamaka and Devon are both lonely, but their parents are different in so many different ways. Her parents work too much, and so does his Mum, so it’s interesting seeing how much they have in common despite their differences.

Interview by Patrick Small

Tomorrow: Part Two. Faridah discusses institutional racism, micro aggressions, sobriety and solitude.

Questions sent in by Anna and Rachel (both Glasgow), Jake (Aberdeen) Clare (Stirling), John (Inverness), Esther (London), Kat (Sheffield), Ron (Atlanta), Beth (Copenhagen) and Mark (Lisbon). If you would like to suggest an author for Product readers to interview please e mail info [at] productmagazine.co.uk or tweet @scottishproduct