Power in the darkness

When Syd Shelton arrived back in London in 1976 after four years working as a photo-journalist in Australia, it was to a city and a country in the thick of change. Margaret Thatcher’s regime as UK Prime Minister may have been three years away, but the seeds of her ascension were already being sewn. Mass unemployment was biting away at working class society, and a growing right wing populism had demonised ethnic communities ever since Tory MP Enoch Powell made his notorious anti-immigration ‘rivers of blood’ speech in 1968. A disaffected youth was already starting to stir and soon a rising punk culture cast aside the old guard of bloated rock stars with a year zero approach craving something faster, louder and more abrasive. Battle lines were drawn when a drunken Eric Clapton ranted his support for Powell to an audience in multi-racial Birmingham during August 1976. Clapton’s guitar playing had been inspired by the blues greats, and he had scored a chart hit with a cover of Bob Marley’s song, I Shot the Sheriff. Neither of these stopped him encouraging the audience to vote for Powell to prevent Britain from becoming a “black colony”, and that Britain should “get the foreigners out, get the wogs out, get the coons out.” Nor did it stop Clapton from repeatedly shouting “Keep Britain White,” the slogan of the National Front, then Britain’s foremost extreme right wing political party.

Out of the appalled response to Clapton’s comments was born Rock Against Racism, a loose-knit collective who launched a campaign to oppose the rise of racist attacks and white nationalism through a series of large-scale open-air carnivals in London, Manchester and elsewhere. Smaller gigs proliferated around the country in a way that brought together the nascent strains of punk and reggae, while RAR’s fanzine, Temporary Hoarding, helped spread the word.

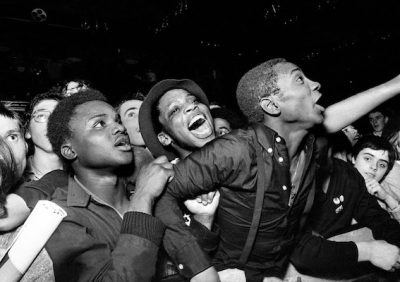

Having met RAR co-founder and fellow photographer Red Saunders, Shelton found himself on the front-line of a movement which for a while at least helped shift the nation’s consciousness and unite various youth cultures through the power of music. This can currently be seen in Rock Against Racism – Photographs by Syd Shelton, a major exhibition of Shelton’s work currently running at Street Level in Glasgow. It’s there in images of artists such as Elvis Costello and Jimmy Pursey onstage at RAR’s open air carnivals as much as it is in the pictures of black youths watching the Specials in 1981. Both evoke an energy drawn from a particular moment in time when political engagement and artistic expression went hand in multi-racial hand.

“You see things in a different way now,” says Shelton. “The clothes people are wearing aren’t outrageous in any way. The bunch of black lads at the Specials gig in Leeds are all wearing Ben Sherman shirts and sta-prest trousers, and they’ve picked up this whole style of the Rude Boys, which had been taken up by skinheads and then taken back by this new generation of Rude Boys that came up through Two Tone. When you make the edit of all that now, because you’ve got more distance you access things in a different way.”

SPECIALS FANS, POTTERNEWTON PARK, LEEDS 1981.

Versions of Shelton’s exhibition have been doing the rounds for several years prior to its current Glasgow run, ever since curator, writer and academic on black British visual culture Carol Tulloch – who also happens to be Shelton’s wife – was offered the opportunity to curate an exhibition of her choice.

“The history of photography is one of archives in drawers waiting for cultural agencies to rediscover them,” says Shelton. “Carol persuaded me to to go through this considerable archive of photographs and memorabilia, and it’s been travelling around on and off since 2008.”

Over five years between 1976 and 1981, Shelton’s camera captured many of RAR’s defining moments. The earliest of these came in spring 1978, when 100,000 people marched from Trafalgar Square to Victoria Park in Hackney behind a lorry on which reggae band Misty in Roots played. Once in Hackney, the crowd watched The Clash headline a bill that included Steel Pulse, X-Ray Spex, The Ruts, Sham 69, Generation X and the Tom Robinson Band. A second carnival at Brockwell Park in Brixton later in the year featured Aswad, Misty in Roots and Elvis Costello and the Attractions.

PAUL SIMONON OF THE CLASH PLAYING THE RAR/ANL CARNIVAL, LONDON IN APRIL 1978

“We didn’t have to beg anyone,” says Shelton. “Everyone wanted to do it. We had a great deal of luck in that respect. It was a very exciting time in our lives.”

Many RAR events were done in tandem with the Anti Nazi League, set up in 1975 by the Socialist Workers Party.

“I don’t think the ANL really got Rock Against Racism,” says Shelton. “They provided help and finance, but I remember when we did the first Carnival, they thought we’d get 20,000 people coming along, and that we could have all the bands playing on a flat-bed truck. We did have flat-bed trucks, which Misty in Roots played on during the march, but when we got to Victoria Park, rather than there being 20,000 people, there was more like 100,000.

“I don’t want to put the Anti Nazi League down, but they had a different agenda. I think they thought Rock Against Racism was the cultural wing of the ANL, but we didn’t see it like that.”

For those plugged in to what was happening, the black RAR star that was the movement’s logo was ubiquitous. It could be worn as a badge of honour on a punky lapel as much as it could be seen emblazoned on the sleeve-notes of the Tom Robinson Band’s 1978 debut album, Power in the Darkness, which included RAR’s founding declaration. In the north-west of England, regional TV presenter Dick Witts, who also played in Manchester band The passage and would go on to run the Camden Festival, wore a Rock Against Racism t-shirt while presenting Granada TV’s arts magazine programme, What’s On?

At around the same time thirty-six miles down the M6, Liverpool hosted a mini carnival in September 1978 at the city’s Walton Hall Park. While no big names played, a local band bill was headlined by Ded Byrds, who featured future Culture Club drummer Jon Moss and guitarist Wayne Hussey, later of the Sisters of Mercy and the Mission. Also on the bill were reggae band Kili Kuri, blues veterans 29th and Dearborn, the Nancy Boys and the Spivs. Radical fringe theatre troupes the Belt and Braves Theatre company and the Sadista Sisters were also in attendance.

As a curious fourteen year old, it was also my first experience of live music, although the spectacle beyond counted just as much. Stalls sold strange smelling food, posters and flyers for the London carnival were free and there was the ubiquitous black star RAR badges too. A similar event was organised the following year. With the new Conservative government just installed, Merseyside Rocking Against Racism ’79 took place at Princes Park, in the far more culturally-diverse Liverpool 8 district, where two years later inner-city riots would prompt the first use of CS Gas on mainland Britain.

LEWISHAM, LONDON. 13 AUGUST 1977. POLICE CHARGE ANTI-RACIST DEMONSTRATORS. LATER IN THE DAY DEMONSTRATORS FIGHT BACK USING BRICKS AND FLARES.

As Shelton points out, however, neither his archive or the exhibition make any claims to be a definitive history of the Rock Against Racism era.

“It’s more an auto-biographical exhibition of my involvement in it,” he says, “and there are big gaps there because of things I didn’t go to. There are no pictures of Scotland, for instance, even though Rock Against Racism had a huge following there. That was evident at the big carnival in Victoria Park, when forty-two coach-loads came down from Scotland.”

To fill in the gaps, accompanying Shelton’s images will be Fragments of RAR Scotland, which will feature images and memorabilia from less lauded Rock Against Racism shows held this side of the border.

Born in Pontefract in South Yorkshire in 1947, Shelton originally studied painting at Leeds College of Art before becoming a photographer and graphic designer. In 1972, he moved to Australia, where he worked as a photojournalist and began to exhibit. Arriving back in England in 1976, he fell in with RAR almost immediately.

“I met Red, who’d written a letter to NME after the Eric Clapton thing, and it got this incredible response,” Shelton remembers, “and that was how the whole thing started. I got involved and I met the other people running it through Red. There was this wonderful mix of writers, fashion designers, graphic designers, photographers and musicians. It was a real melting pot of creativity, so it certainly wasn’t a drudge. It was fun. We’d have been going to all these gigs by Steel Pulse anyway. Music was a really big part of our lives.

“RAR was very much a DIY operation. We had an office, but really there was no hierarchy as such. Temporary Hoarding was there to tell you how to do things, and if you agreed with anti-racism and cultural warfare if you like, you could put on a badge, put on a gig and just do it. That was the magic of it. It wasn’t organised nearly as much as you might think. In that five years between 1976 and 1981, no-one ever sat down and planned anything. We didn’t know how long it would go on for. At that time we were far too involved in everything that was going on.”

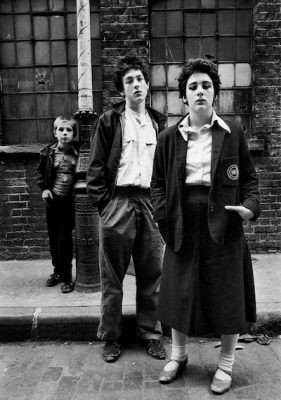

RAR FANS, BETHNAL GREEN, EAST LONDON 1978.

While RAR defined its time, within a few years the organisation came to a natural close.

“I remember Jerry Dammers saying to me that we’d kind of taken over,” says Shelton. “Multi-racial bands had become the norm, so there maybe wasn’t as much need for Rock Against Racism as there once had been. Also, we were exhausted. By 1981 we all had kids, and touring round the country with bands was much more difficult than it had been. The idea of Rock Against Racism had caught the imagination with Two Tone, and we didn’t need it anymore.”

While Rock Against Racism was revived as Love Music Hate Racism in 2002, it has never quite captured the zeitgeist in the way RAR did.

“You can’t just take ideas from a particular time and try and repeat it,” says Shelton. “There was a genuine grassroots thing going on in the 1970s, and things have changed in a way that I don’t think things can happen like that again.”

Shelton admits, however, that “In some ways the times we’re going through now are very similar to the 1970s. We were going through the first big recession since the war, and James Callaghan who was the Labour Prime Minister was making these stringent cuts, but we were lucky. In punk and reggae we had these two great rebel musics coming out of the 1970s. Up until then, black bands tended to play to black audiences, and it was the same for white bands. I remember going to see a black band in Dalston and being one of only two white people there.”

[quote]All that xenophobia has been normalised again, so we still have to fight[/quote]

“It was a time as well when there were only two black footballers playing professionally in Britain, which is unthinkable now, but the act of putting black and white musicians on the same stage, the theatrical symbolism of that, was a political act in itself. You didn’t need slogans. And when Steel Pulse came on and did their song Ku Klux Klan, while wearing KKK outfits, it was jaw-dropping.”

Almost forty years on, the times may be different, but Shelton’s exhibition is not only a vital document of a critical mass in terms of youth culture, politics and music. It also highlights the need for something similar to Rock Against Racism today.

“We’re now living in these crazy times of Brexit, Trump, the NF in France,” Shelton points out. “All that xenophobia has been normalised again, so we still have to fight. It’s not as easy to fight now as it was in what were phenomenally rebellious times, but recently looking at the anti Trump marches, it’s been mind-blowing. Looking at the placards as well, it’s not all SWP anymore.”

“The spontaneous response to Trump has been tremendous. To see the number of people on the street was amazing. It came when it was least expected, and that’s when things change.”

All images: Copyright Syd Shelton. Courtesy of the artist and Autograph ABP.

Rock Against Racism – Photographs by Syd Shelton, Street Level Photoworks, Glasgow, until April 9th. Presented in Partnership with Autograph ABP.

Fragments of RAR Scotland, Trongate 103, February 11th-March 26th.

A series of talks and presentations on Scotland’s role in Rock Against Racism will take place on Saturday April 1st, 2-5pm.