Blind vision

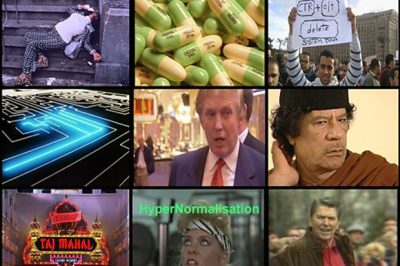

With its pulsing soundtrack and Twin Peaks–style psychedelia, Adam Curtis’ latest documentary announces its intention to disturb in no uncertain terms. However, close your eyes and listen to Curtis’ school-teacher voice, and he could be reading from a history book, so precise and tidy are his explanations for the precarious situation the modern world finds itself in. HyperNormalisation builds on his past work such as Bitter Lake, which attempted to explain the political situation in Afghanistan, and Pandora’s Box, about the legacy of technocrats in the political sphere. This newest documentary attempts to use its eponymous concept to explain previously incomprehensible and ceaselessly terrifying phenomena such as Brexit and Trump by piecing together archive footage from news stories and films. The term ‘hypernormal’ was coined by the Soviet writer Alexei Yurchak, to describe the position that Soviet citizens found themselves in whereby they knew that everything their leaders were telling them was wrong, but accepted it as truth. A case in point was the Soviet leadership’s claims of economic prosperity, relayed to starving people having punch-ups in food queues. The documentary starts in 1975 with the twin events of the discussions between Henry Kissinger and Hafez al-Assad in Syria and the fiscal crisis in the US, and ricochets through all the major plot points of the last 40 years before landing squarely in Brexit and the current US elections.

The film is fascinating and enthralling. It’s not so much a polemic as a calm and rational explanation of how we’ve got to where we are. It doesn’t attempt to offer answers, or particularly to critique the actions of historical leaders. It even has a sense of humour, albeit a dark one, juxtaposing footage of a woman being arrested with a workout video featuring Jane Fonda. In many ways it’s a wide-eyed and astute sociological study.

However, it’s also – for a narrative that takes in several Middle Eastern dictators, the birth of suicide bombing and looming Trumpageddon – a little too comfortable. It’s easy to gulp down the film as a tidy potted history of the past few years that draws lines between people and events with a ruler. Interestingly, in an interview with The New York Times, Curtis remarked that ‘What really happens is the key thing; you mustn’t try and force the reality in front of you into a predictable story. What you should do is notice what is happening in front of your eyes, and what instinctively your reaction is’. This is simultaneously ironic and appropriate in relation to Curtis’ work. On the one hand, it rather seems Curtis has had a hypothesis in mind before doing his research, and that he has very much brought the story to him rather than the other way round, rejecting facts and figure that would leave strings hanging. On the other hand, the stories he produces are certainly unpredictable. Whilst HyperNormalisation isn’t made up, exactly, it definitely takes the viewer on a ride through the unexpected; one of his central arguments is that Gaddaffi is an ‘imaginary villain’, scapegoated by the West to avoid them having to confront the problems in the Middle East head on. This is slightly spurious considering Gaddafi had built a reputation as an autocratic human rights abuser long before the US decided to blame him, correctly or not, for the Lockerbie bombing.

Jonathan Lethem, author of The New York Times article, commented that Curtis ‘pursues the art of the wild leap’, a somewhat coy way of suggesting that not all of Curtis’ suggestions are founded. He makes you question how you didn’t know any of this before, and then realise that you still don’t know any of this, because a lot of it is supposition and clever editing. The viewer is presented with something that they want – an explanation – although at the same time as they are made aware, through the welding together of BBC archive footage and film scenes, that this is a fabrication – creating a cognitive dissonance very similar to that which ‘hypernormalisation’ refers to, in fact.

However, it’s this sort of intellectual conspiracy that’s marked Curtis’ work out from the beginning. He calls himself a journalist but doesn’t pretend to be an expert. How harmful, then, is the slightly scattergun approach to the truth evidenced in HyperNormalisation and his other documentaries? It’s easy to argue that they’re intellectual diversions, aiming to provide food for thought rather than definitive answers. Also, it’s hard to knock on the door of a thesis so tight, convincing and entertaining with the squeaky reminder that the argument has holes, especially when the alternative is a foggy incomprehensibility at the global political squalor we find ourselves mired in. Still, if it isn’t watertight, HyperNormalisation begs the question how much we can learn from it, and how useful it is as a piece of socio-political commentary.

For a start, the title alone intellectualises world politics in a way that is at best unhelpful, and at worst elitist. ‘Hypernormal’ is a thorny word for what is essentially a common psychological response, that of accepting the words of people in authority, even if you know they’re false, and defaulting to the least complicated method of action, even if that is blind acceptance. (Yurchak’s use of the word is slightly more nuanced, but this is essentially the implications of the definition that Curtis boils it down to). Wrapping this up under a term is enlightening in so far as it allows Curtis to sum up a general trend, but is unhelpful in that it wreaks slightly of conspiracy and hysteria, even in Curtis’ flat, unruffled tone, and has to be unpacked and contextualised before it makes sense. Curtis’ use of the term also implies that this is a new phenomenon, whilst this isn’t the first time the world has found itself with a bewildered political class and a general sense that the unthinkable is happening.

Similarly, you do wonder whether a film with a completely different argument could have been made about the same period, simply by collecting up and re-arranging the off-cuts. However, Curtis makes a notable observation that the Occupy movement was not about an idea so much as it was about implementing a new system of management. In a way, the documentary is constructed along the same lines, as it re-organises the manner in which we view history, drawing lines between events and people in a style akin to a human resources manager tasked with the restructuring of a large corporation. Certain connections, such as his argument that the intended ethos of cyberspace grew from the LSD subculture of the 1960s, are fascinating in their own right, and enrich consideration of where cyberspace is now. And, perhaps, this is the point. Curtis isn’t trying to convince you of anything. He’s making a story, and making you think, as he’s aware, as a documentary maker – not as a philosopher, an academic, or a messiah – that’s all he can really do.